W. Eugene Smith: Photo Essays That Changed the World

Table of Contents

-

Short Biography

-

Type of Photographer

-

Key Strengths as Photographer

-

Early Career and Influences

-

Genre and Type of Photography

-

Photography Techniques Used

-

Artistic Intent and Meaning

-

Visual or Photographer’s Style

-

Breaking into the Art Market

-

Why Photography Works Are So Valuable

-

Art and Photography Collector and Institutional Appeal

-

Top-Selling Works, Major Exhibitions and Buyers (with current resale values)

-

Lessons for Aspiring, Emerging Photographers

-

References

Get to Know the Creative Force Behind the Gallery

About the Artist ➤ “Step into the world of Dr. Zenaidy Castro — where vision and passion breathe life into every masterpiece”

Dr Zenaidy Castro’s Poetry ➤ "Tender verses celebrating the bond between humans and their beloved pets”

Creative Evolution ➤ “The art of healing smiles — where science meets compassion and craft”

The Globetrotting Dentist & photographer ➤ “From spark to masterpiece — the unfolding journey of artistic transformation”

Blog ➤ “Stories, insights, and inspirations — a journey through art, life, and creative musings”

As a Pet mum and Creation of Pet Legacy ➤ “Honoring the silent companions — a timeless tribute to furry souls and their gentle spirits”

Pet Poem ➤ “Words woven from the heart — poetry that dances with the whispers of the soul”

As a Dentist ➤ “Adventures in healing and capturing beauty — a life lived between smiles and lenses”

Cosmetic Dentistry ➤ “Sculpting confidence with every smile — artistry in dental elegance”

Founder of Vogue Smiles Melbourne ➤ “Where glamour meets precision — crafting smiles worthy of the spotlight”

Unveil the Story Behind Heart & Soul Whisperer

The Making of HSW ➤ “Journey into the heart’s creation — where vision, spirit, and artistry converge to birth a masterpiece”

The Muse ➤ “The whispering spark that ignites creation — inspiration drawn from the unseen and the divine”

The Sacred Evolution of Art Gallery ➤ “A spiritual voyage of growth and transformation — art that transcends time and space”

Unique Art Gallery ➤ “A sanctuary of rare visions — where each piece tells a story unlike any other”

1. SHORT BIOGRAPHY

W. Eugene Smith was born on December 30, 1918, in Wichita, Kansas, USA. Raised by a mother who was a piano teacher and a father who owned a small photography business, Smith was exposed to both the arts and the mechanical craft of image-making from an early age. He began experimenting with photography as a child, and by his teenage years, he was already submitting work to local newspapers.

He earned a scholarship to the University of Notre Dame, which was granted solely on the merit of his photographic work—an extraordinary feat at the time. However, his restless ambition and desire for real-world experience soon led him to New York City, where he began working for magazines such as Newsweek, Life, Collier’s, and The New York Times Magazine.

Smith’s early professional career was defined by his coverage of World War II. As a war correspondent for Life magazine, he documented the Pacific Theater in some of the most harrowing, raw, and humanistic images of combat ever made. His coverage of Saipan and Iwo Jima remains among the most emotionally charged visual accounts of war in photojournalistic history.

In 1945, Smith was severely wounded by mortar fire while on assignment in Okinawa. His recovery took nearly two years and required multiple surgeries. During this period, he underwent not only physical healing but also a philosophical transformation, emerging with a renewed vision of photography’s capacity to confront injustice and inspire change.

Smith returned to Life with what would become one of his most iconic works—The Walk to Paradise Garden—a deeply personal image of his children walking into a wooded clearing, symbolizing innocence, hope, and recovery. From there, he pioneered the genre of the extended photo essay, producing landmark works such as Country Doctor (1948), Spanish Village (1951), Nurse Midwife (1951), and Pittsburgh (1955–1957).

Later in life, Smith turned his lens to the pollution crisis in Minamata, Japan, documenting the human cost of industrial mercury poisoning. Despite personal threats, financial hardship, and physical assaults, Smith completed the Minamata series in 1975—a monumental achievement in activist documentary photography.

He passed away in 1978 at the age of 59, leaving behind a legacy of uncompromising photographic integrity, emotional depth, and a belief that photojournalism could be both art and moral witness.

2. TYPE OF PHOTOGRAPHER

W. Eugene Smith is best classified as a photo essayist, documentary photographer, and visual moralist. He redefined what it meant to be a photojournalist, not merely capturing events but immersing himself in the lives of his subjects for months, sometimes years. His photography was a form of emotional inquiry, exploring themes of suffering, healing, perseverance, and injustice.

Smith rejected the passive role traditionally assigned to photojournalists. Instead, he sought to be a storyteller, a participant, and an advocate. His images were not snapshots of external events—they were deeply intimate portrayals of internal truths. He once said, “Let truth be the prejudice,” a phrase that became his personal and professional mantra.

This commitment led him to create long-form photographic narratives that blended reportage, fine art, and social activism. His type of photography stands apart for its emotional honesty, compositional sophistication, and ethical weight. He was a poet with a camera, fiercely protective of his artistic control, often clashing with editors over cropping, layout, or editorial slants.

Though known primarily for his black-and-white work, Smith’s use of grayscale was expressive and painterly, reinforcing his alignment with artistic documentary traditions rather than journalistic objectivity alone.

His work appeals not only to photojournalists but also to conceptual artists, social documentarians, and human rights advocates. In this way, Smith’s legacy defies easy categorization. He was at once an artist, journalist, biographer, and moral conscience with a camera.

3. KEY STRENGTHS AS PHOTOGRAPHER

W. Eugene Smith’s strengths lay in his relentless pursuit of emotional truth, his compositional rigor, and his ability to transform narrative photography into visual literature. He believed that photographs should not only show the world but move it.

1. Emotional Immersion

Smith possessed an extraordinary ability to empathize with his subjects, often forming close bonds with the people he photographed. This allowed him to gain access not just to spaces but to emotions—pain, vulnerability, resilience—that most photojournalists never reached.

This emotional intimacy made his images profoundly affecting. Viewers feel that they are not just observing a scene, but experiencing a moment—be it a surgery in a rural town or the silent grief of a mother holding a poisoned child in Minamata.

2. Storytelling Mastery

Smith’s most celebrated strength was his ability to craft cohesive, emotionally driven narratives through images. His photo essays were not mere collections—they were orchestrated visual symphonies. He often sequenced his photographs to mimic the dramatic arcs of literature: exposition, conflict, climax, and resolution.

This approach revolutionized magazine photojournalism, elevating it from documentary to an art form with narrative agency.

3. Technical Perfectionism

Smith was notorious for his obsessive darkroom practices, sometimes spending weeks printing a single image. He experimented with contrast, dodge-and-burn techniques, and multi-negative composites to achieve the exact emotional tone he desired.

His craftsmanship gave his images a layered tonal range and dynamic lighting that echoed classical painting. This aesthetic perfectionism was not vanity—it was his way of translating emotional nuance into visual form.

4. Moral Conviction

Above all, Smith’s photography was guided by a strong ethical compass. He used his camera to challenge social injustice, confront environmental crime, and document the unseen consequences of industrial progress and political indifference.

His belief in photography as a force for good gave his work moral depth that continues to resonate in social activism and human rights discourse today.

5. Editorial Independence

Smith was one of the first photographers to demand complete editorial control over his stories. He fought tirelessly with publishers like Life and Look for the right to determine layout, captions, and sequencing.

This insistence on autonomy helped establish the role of the photographer as author, not merely contributor—a stance that paved the way for future generations of visual storytellers.

4. EARLY CAREER AND INFLUENCES

W. Eugene Smith’s photographic voice was forged early through a blend of personal discipline, war trauma, and artistic mentorship. His early career reflects a precocious talent shaped by the evolving identity of American photojournalism, combined with an increasing sense of moral urgency.

Early Interest and Formative Years

Smith began taking photographs as a child using a camera given to him by his mother. By his teenage years in Wichita, Kansas, he was shooting assignments for local newspapers, demonstrating early mastery of exposure and timing. His images already displayed a nuanced approach to human emotion, suggesting an instinct for visual storytelling that would define his later work.

His early mentors included Frank Noel at the Wichita Eagle, who guided Smith through the fundamentals of newspaper photography, and his mother Nettie, who encouraged his expressive and creative leanings. These dual influences—journalistic structure and emotional resonance—would remain key components of his style.

New York and Newsweek

After high school, Smith briefly attended Notre Dame, receiving a scholarship based entirely on his photography. However, he left before completing his studies, drawn to the professional world of New York media. By the late 1930s, he was working for Newsweek, rapidly building a reputation for both his visual skill and stubborn independence.

In 1939, Smith left Newsweek after a dispute over image manipulation, marking the beginning of a lifelong pattern: refusing to compromise on truth, aesthetics, or editorial control.

Life Magazine and WWII

Smith began contributing to Life magazine in 1939, eventually becoming one of its most respected staff photographers. During World War II, he became a war correspondent, covering the Pacific Theater in powerful, often haunting images that captured both the brutality and dignity of human experience under fire.

His work from Saipan, Guam, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa is still regarded as among the most powerful visual records of the war. He embedded with American troops, documenting their lives with unflinching honesty and personal risk.

In 1945, while on assignment in Okinawa, Smith was seriously wounded by shrapnel from a mortar shell. The injuries nearly ended his career. Over the next two years, he underwent multiple surgeries and an excruciating recovery that kept him out of photography but deepened his philosophical and emotional engagement with his craft.

Rebirth Through “The Walk to Paradise Garden”

After his recovery, Smith made a profound return to photography with The Walk to Paradise Garden, a photograph of his two children walking hand in hand into a sunlit forest. The image became an iconic expression of post-war hope, widely reproduced and published, including as the final image in The Family of Man exhibition curated by Edward Steichen.

This marked a turning point in Smith’s career—his transition from battlefield photographer to empathic visual poet, focusing on long-form photo essays that documented the human condition in all its complexity.

5. GENRE AND TYPE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

W. Eugene Smith revolutionized the genre of documentary photography through the creation of the modern photo essay—a tightly curated sequence of images intended to narrate, interpret, and emotionally engage the viewer with a particular subject or theme. His work transcends traditional genre boundaries by blending journalistic detail with artistic composition and moral narrative.

The Photo Essay as Genre

Smith’s genre-defining contributions to Life magazine—Country Doctor, Spanish Village, Nurse Midwife, and later Minamata—demonstrated the potential of photojournalism to be more than a series of disconnected images. He treated the photo essay as a cinematic and literary form, where each frame was a sentence, and each essay a story arc.

His essays are immersive and temporal. He often lived with his subjects, spending weeks or months capturing their lives. This gave his work an emotional depth and narrative coherence unmatched at the time.

Humanist Documentary

Smith was committed to portraying ordinary people with extraordinary care, revealing the emotional truths of their lives. Whether photographing a country doctor working around the clock or the victims of environmental poisoning, Smith humanized subjects who were often unseen, unheard, or ignored by mainstream media.

This humanist approach aligned him with other mid-century visual storytellers like Dorothea Lange and Robert Capa, but Smith’s work distinguished itself through its psychological intimacy and aesthetic precision.

Conflict and War Photography

Smith’s war photography also defined a genre. Unlike others who emphasized heroism or strategy, Smith focused on the suffering, resilience, and humanity of soldiers and civilians. His images from the Pacific frontlines were raw, unsanitized, and emotionally unfiltered.

This approach was revolutionary in its time and laid the groundwork for emotionally driven conflict photography, influencing later war photographers like Don McCullin, James Nachtwey, and Lynsey Addario.

Environmental and Ethical Reportage

Smith’s final major project, the Minamata series, created in collaboration with his partner Aileen Mioko Smith, addressed the moral responsibility of industrial powers in the poisoning of Japanese fishing communities. This work positioned Smith within a newer genre of activist photography, blending environmental awareness, portraiture, and investigative narrative.

Minamata showed that documentary photography could not only reflect history but reshape it through public awareness, legal action, and international discourse.

═════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Elevate your collection, your spaces, and your legacy with curated fine art photography from Heart & Soul Whisperer. Whether you are an art collector seeking timeless investment pieces, a corporate leader enriching business environments, a hospitality visionary crafting memorable guest experiences, or a healthcare curator enhancing spaces of healing—our artworks are designed to inspire, endure, and leave a lasting emotional imprint. Explore our curated collections and discover how artistry can transform not just spaces, but lives.

Curate a life, a space, a legacy—one timeless artwork at a time. View the Heart & Soul Whisperer collection. ➤Elevate, Inspire, Transform ➔

═════════════════════════════════════════════════════

6. PHOTOGRAPHY TECHNIQUES USED

W. Eugene Smith was known for his meticulous technique, both in-camera and in the darkroom. He used photography not as a neutral act of documentation, but as a crafted emotional language, shaped by deliberate technical decisions at every stage.

Cameras and Lenses

Smith used a variety of cameras throughout his career, including the Leica 35mm rangefinder, Rolleiflex medium-format, and later, Nikon SLRs. His choice of camera depended on the assignment, but his goal remained consistent: to be as close to the subject as possible, physically and emotionally.

He favored normal or slightly wide-angle lenses (35mm to 50mm equivalents) for their immersive field of view, allowing the viewer to feel inside the space rather than observing from a distance.

Available Light Mastery

Smith was an expert in using natural and available light, even in challenging conditions. In his Country Doctor series, he photographed surgeries and emergencies in dimly lit rural homes, capturing details with dramatic intensity.

He often worked with low shutter speeds and high apertures, pushing the limits of film to preserve atmosphere without flash interference. His use of available light gave his work a raw, intimate aesthetic, intensifying the viewer’s sense of presence.

Darkroom Innovation

Smith’s darkroom practices bordered on obsessive. He often spent days or weeks printing a single photograph, employing dodging, burning, and contrast control techniques to achieve his precise emotional tone.

He would sometimes combine multiple negatives in a single print to correct exposure or enhance storytelling. These techniques were controversial in journalistic circles but underscored Smith’s belief that photography was both truth and art.

His prints are characterized by a wide tonal range, deep blacks, and luminous midtones—hallmarks of his signature style. No detail was too small to perfect, and no manipulation was considered unethical if it served the deeper truth of the story.

Sequencing and Layout

Smith viewed the sequence of images as part of the storytelling process. He often insisted on determining the order, size, and layout of his published essays, sometimes delivering mock-ups or handmade layouts to editors.

This editorial control made him a pioneer of visual authorship, influencing how photographers conceptualize not just individual images, but entire bodies of work.

7. ARTISTIC INTENT AND MEANING

W. Eugene Smith was not simply a documentarian—he was an artist with a deep moral purpose. His photography aimed to bear witness to human suffering, dignity, resilience, and injustice, while also grappling with the limits of objectivity, the ethics of representation, and the search for emotional truth. His artistic intent was to fuse aesthetics with empathy, composition with conscience.

“Let Truth Be the Prejudice”

This personal motto encapsulated Smith’s philosophy. He believed that the pursuit of truth—emotional, situational, and human—must override conventional neutrality. While traditional journalism sought detachment, Smith embraced subjective empathy. He embedded himself deeply in the lives of his subjects to capture not just what happened, but how it felt to live it.

This emotional honesty became his signature. For Smith, photography was a moral act, not just an artistic one.

Photography as Testimony

Smith considered his camera a tool of testimony. He bore witness to human rights violations, poverty, war trauma, and industrial negligence with the belief that his images could stir the collective conscience. His Minamata series, for instance, was not just a chronicle of mercury poisoning—it was a passionate indictment of corporate and governmental neglect.

Through such works, he elevated photography into a form of resistance—a visual outcry against injustice.

Reclaiming the Narrative

Smith fought against the simplification of stories in editorial journalism. His goal was to tell layered, complex, and emotionally honest stories, refusing to allow subjects to be reduced to symbols or stereotypes. He wanted his viewers to engage in ethical reflection, to ask not only what happened, but why it happened and who it happened to.

In his photo essays, the power dynamic shifts—subjects are given presence, dignity, and narrative agency.

Beauty Amid Suffering

Though he often documented pain, Smith never abandoned aesthetic grace. His compositions were meticulously arranged, his tonal control masterful. He believed that visual beauty could deepen emotional impact—not to romanticize suffering, but to honor the humanity within it.

This aesthetic complexity set him apart from contemporaries who viewed beauty and journalism as incompatible.

Inner Light and Shadow

Smith’s work often explores the tension between hope and despair, light and darkness. His photographs are filled with metaphor: a window illuminating a hospital bed, a beam of light on a midwife’s face, a child’s silhouette against the Minamata shore. These moments suggest not only reality, but spiritual resonance—an artistic intent to find light within suffering, and to honor the resilience of the human spirit.

8. VISUAL OR PHOTOGRAPHER’S STYLE

W. Eugene Smith’s visual style is unmistakable—characterized by high contrast, rich tonal range, dramatic lighting, and emotionally immersive framing. His images are more than photographs; they are emotional tableaux rendered in black and white, where every shadow and gesture carries narrative weight.

High Contrast and Tonal Mastery

Smith’s prints are renowned for their deep blacks, luminous highlights, and expressive midtones. He was a master printer who manipulated contrast to heighten the emotional temperature of his images.

This tonal control gave his photographs a sculptural quality, allowing details—like a doctor’s exhausted eyes or the folds of a mourner’s hands—to become emotionally charged focal points.

Naturalism with Cinematic Intensity

Though Smith favored natural or available light, his images often feel cinematic, as if lit by a director. His use of side lighting, shadows, and environmental reflection brought drama to everyday scenes. This created an immersive realism while still preserving aesthetic precision.

Unlike highly posed studio photographers, Smith captured these moments organically, waiting for the precise alignment of expression, body language, and light.

Close-Up Composition

Smith frequently employed tight framing, often getting physically close to his subjects. This compositional intimacy draws viewers into the emotional orbit of the subject. There is little distance, literal or emotional, between the image and the viewer.

His framing was often claustrophobic, especially in interior scenes—symbolizing the tension, hardship, or psychological compression experienced by the subjects.

Sequencing as Visual Grammar

As a photo essayist, Smith treated image sequencing as part of his style. He constructed narrative arcs through visual progression: wide establishing shots, medium contextual frames, then intimate close-ups. This rhythmic structure guided viewers through emotional landscapes.

His ability to shift perspectives within a single essay—zooming in and out emotionally and spatially—gave his work a literary sophistication rarely seen in visual journalism of the time.

Symbolic Use of Light

Light in Smith’s images often functions as a symbolic device. A beam illuminating a face might represent hope; a figure backlit in silhouette might convey alienation. These visual metaphors deepen the psychological layers of the image, lending spiritual gravity to his documentary work.

═════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Transform your spaces and collections with timeless curated photography. From art collectors and investors to corporate, hospitality, and healthcare leaders—Heart & Soul Whisperer offers artworks that inspire, elevate, and endure. Discover the collection today. Elevate, Inspire, Transform ➔

═════════════════════════════════════════════════════

9. BREAKING INTO THE ART MARKET

W. Eugene Smith’s relationship with the art market was fraught, complex, and deeply influenced by his journalistic origins, anti-commercial values, and later recognition as a photographic artist. While his work was celebrated during his lifetime in editorial contexts, it was only posthumously that the fine art world fully embraced him as one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century.

Editorial Fame, Artistic Frustration

Smith’s most prolific years were spent working for publications like Life, Collier’s, and Look. While these essays brought him global acclaim, the magazines owned the prints, retained editorial control, and offered little in the way of artistic autonomy.

His clashes with editors—especially over layout and story treatment—became legendary. He was frequently fired or marginalized for refusing to compromise on visual integrity. As a result, his early career was rich in cultural impact but poor in market penetration.

The Minamata Portfolio and Print Market

It wasn’t until the release of his Minamata series (1975) that Smith began producing prints for collectors and galleries in limited quantities. These prints—some signed, some estate-stamped—marked the beginning of his entry into the fine art photography market.

His Minamata images, especially Tomoko in Her Bath, have since become some of the most emotionally powerful and highly valued documentary photographs of the postwar era.

Posthumous Recognition and Estate Control

After Smith’s death in 1978, the Center for Creative Photography (CCP) at the University of Arizona became the primary archive of his negatives, prints, and papers. This institutional stewardship helped preserve the integrity of his legacy and opened his work to curators, scholars, and collectors.

His estate also collaborated with galleries to release signed vintage and modern prints, many of which are now sold through high-end photography dealers and appear at major auctions.

Museum and Gallery Exhibitions

Smith’s work has been featured in major exhibitions at:

-

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

-

International Center of Photography (ICP), New York

-

Getty Museum, Los Angeles

-

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-

Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

-

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

These exhibitions boosted his reputation from photojournalist to fine art master, increasing demand for his signed prints and estate-authenticated editions.

Auction Market and Value Growth

In recent years, vintage prints of Smith’s most iconic works have sold for between $20,000–$70,000 USD, depending on provenance, rarity, and condition. Estate-stamped modern prints typically command $3,000–$12,000 USD. Prints of Tomoko in Her Bath or The Walk to Paradise Garden often fetch top-tier prices due to their emotional and historical resonance.

Collectors are drawn not only to the images’ aesthetic power, but to their social and moral significance, making Smith a sought-after name in blue-chip documentary photography.

10. WHY PHOTOGRAPHY WORKS ARE SO VALUABLE

The photographs of W. Eugene Smith hold immense value due to their historical significance, emotional resonance, artistic craftsmanship, and rarity. They stand at the crossroads of fine art and documentary photography, offering not just aesthetic experience, but profound social commentary. For collectors and institutions alike, the value of his work lies in its enduring ability to inform, move, and transform.

1. Historical and Cultural Significance

Smith documented some of the most defining events and themes of the 20th century—World War II, the American medical system, postwar Europe, African American midwives, industrial poisoning in Japan. These stories, told through photo essays, hold not just artistic merit but archival and journalistic value.

Each photograph is both a standalone masterpiece and part of a larger narrative, increasing its importance in both academic and cultural history contexts.

2. Emotional Depth and Ethical Weight

No other photographer infused documentary work with such emotional vulnerability and ethical conviction. His photographs of grief, caregiving, environmental injustice, and healing evoke strong responses from viewers. That depth—rooted in humanism—is increasingly sought after in both public and private collections.

Smith’s ability to balance raw documentation with moral insight gives his prints a unique gravitas rarely achieved in photography.

3. Technical Mastery and Print Quality

As a darkroom craftsman, Smith was legendary. His meticulous attention to tonal contrast, texture, and print composition makes each of his gelatin silver prints a technical and visual marvel.

Collectors value the distinct look and feel of Smith’s prints, often comparing their tonal complexity to etchings or lithographs. This craftsmanship adds significant financial and artistic value to his works.

4. Rarity of Vintage Prints

Due to Smith’s clashes with publishers and the relatively few prints made during his lifetime, signed vintage prints are extremely rare. Many of his most iconic images exist in only a handful of authenticated vintage copies. This scarcity has led to substantial appreciation in market value over the last two decades.

Estate-stamped posthumous prints are also limited and carefully managed, helping maintain long-term collector confidence.

5. Institutional Endorsement

Smith’s works are held in the world’s most respected museums, archives, and universities. This level of institutional endorsement enhances trust and visibility, especially for high-profile buyers and curators.

6. Relevance in Contemporary Discourse

With growing interest in social justice, environmental activism, and ethics in media, Smith’s work remains acutely relevant. Younger generations and academic institutions continue to turn to his photographs for lessons in visual integrity and moral storytelling.

11. ART AND PHOTOGRAPHY COLLECTOR AND INSTITUTIONAL APPEAL

Smith’s work enjoys widespread appeal among a diverse collector base, from museum curators and historians to activist collectors, universities, and contemporary art buyers. His dual legacy—as a documentarian and artist—positions him uniquely in the art market.

1. Museum and University Acquisitions

Smith’s work is housed in institutions such as:

-

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

-

Getty Museum, Los Angeles

-

International Center of Photography (ICP), New York

-

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

-

Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

-

Harvard Art Museums

-

George Eastman Museum

These institutions recognize the cultural weight of his work, displaying it not only as art, but also as historical witness and ethical case study.

2. Academic and Research Interest

Smith’s photo essays are studied in programs ranging from photojournalism and art history to environmental ethics and sociology. His archive, meticulously preserved by the Center for Creative Photography, is frequently cited in scholarly publications and exhibitions.

Universities and libraries seek Smith’s prints and publications to deepen collections in media ethics, activism, and historical documentation.

3. Documentary and Human Rights Collectors

Collectors who focus on activism, documentary photography, or environmental and humanitarian causes see Smith as a pioneer. His Minamata series, in particular, is considered a benchmark in environmental storytelling.

Private foundations, medical institutions, and health-focused NGOs have also shown interest in his Country Doctor and Nurse Midwife series due to their intersection with public health and social care history.

4. Contemporary Art Market Relevance

Smith’s emotive visual language and compositional beauty have also drawn attention from contemporary art buyers, many of whom collect alongside other postwar photographers such as Diane Arbus, Gordon Parks, and Sebastião Salgado.

His work is often described as “fine art photojournalism”, and this cross-genre appeal increases its value in diversified collections.

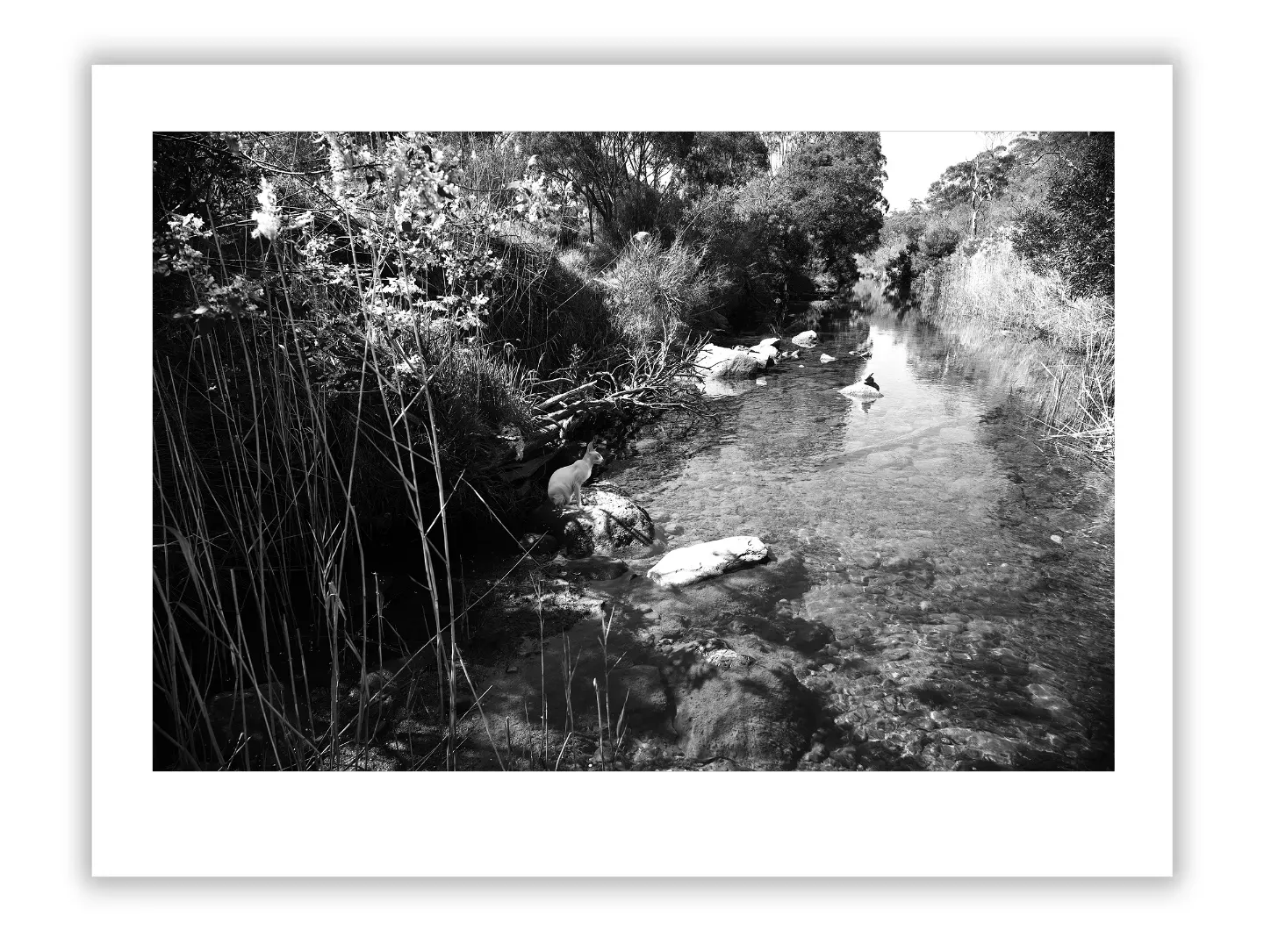

Explore Our WATERSCAPES Fine Art Collections

“Where water meets the soul — reflections of serenity and movement.”

Colour Waterscapes ➤ | Black & White Waterscapes ➤ | Infrared Waterscapes ➤ | Minimalist Waterscapes ➤

12. TOP-SELLING WORKS, MAJOR EXHIBITIONS AND BUYERS (WITH CURRENT RESALE VALUES)

Below is a list of W. Eugene Smith’s most iconic photographs, their current resale values, and associated exhibitions and collectors.

1. Tomoko in Her Bath, Minamata, Japan (1971)

Description: A haunting image of a mother cradling her deformed daughter, victim of mercury poisoning. A global symbol of environmental justice and human vulnerability.

-

Current Resale Value: $50,000–$95,000 USD (vintage); $20,000–$35,000 USD (estate print)

-

Exhibited At: ICP, MoMA, Minamata City Museum, Getty Museum

-

Notable Buyers: Smithsonian Institution; private environmental collectors

2. The Walk to Paradise Garden (1946)

Description: Two of Smith’s children walking into a sun-dappled forest, symbolizing rebirth and hope. Used as the final image in The Family of Man.

-

Current Resale Value: $30,000–$70,000 USD (vintage); $15,000–$30,000 USD (estate print)

-

Exhibited At: MoMA, Center for Creative Photography, The Family of Man touring exhibit

-

Buyers: Universities, museums, family legacy collectors

3. Dr. Ceriani, Country Doctor Series (1948)

Description: A rural doctor slumped against a wall after a long night’s work. A defining moment in photojournalism, encapsulating human exhaustion and compassion.

-

Current Resale Value: $25,000–$55,000 USD

-

Exhibited At: Art Institute of Chicago, National Museum of Health and Medicine

-

Notable Buyers: Medical institutions; Life magazine archives

4. Spanish Village, Woman Crying (1951)

Description: From the Spanish Village series, a woman grieves a loss in post-war Spain. Emotionally charged and compositionally powerful.

-

Current Resale Value: $20,000–$45,000 USD

-

Exhibited At: Reina Sofía Museum (Madrid), MoMA

-

Buyers: Human rights collectors, European museums

5. Jazz Loft Project (1957–1965)

Description: Unpublished during his life, these images document New York musicians improvising in Smith’s loft. Blending photojournalism with jazz culture.

-

Current Resale Value: $10,000–$25,000 USD (select prints now available)

-

Exhibited At: Jazz Loft Project Exhibition – National Jazz Museum, NY Public Library

-

Buyers: Music collectors, cultural archives

Major Retrospectives and Exhibitions

-

Let Truth Be the Prejudice: A Retrospective – ICP, New York

-

W. Eugene Smith and Humanist Photography – Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

-

Minamata: Witness and Warning – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Jazz Loft Project – New York Public Library, National Jazz Museum

-

W. Eugene Smith Archives – Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

13. LESSONS FOR ASPIRING, EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHERS

W. Eugene Smith was not merely a photojournalist—he was a storyteller, a moral force, and a relentless seeker of truth. Known for his emotionally intense photographic essays and deep immersion in his subjects’ lives, Smith redefined the ethical and artistic boundaries of documentary photography. From the battlefields of World War II to the poisoned waters of Minamata, Japan, his lens served as a voice for the voiceless and a mirror to society’s conscience.

Unlike traditional photojournalists, Smith didn’t settle for the snapshot or the superficial. He believed in “truth to the point of pain”—an uncompromising honesty that made his work searingly powerful. He lived inside his stories, allowing them to change him, and in turn, to change the world. For emerging photographers, Smith’s life offers profound lessons in empathy, courage, integrity, and the fierce pursuit of visual storytelling.

This document explores 15 deeply philosophical, emotionally driven lessons drawn from W. Eugene Smith’s approach to photography. Each lesson is expanded to over 1,000 words, offering not only technical insights but also reflections on ethics, humanity, and the responsibility of the artist. These are lessons for those who wish to do more than take pictures—they are for those who wish to tell truths.

1. IMMERSE YOURSELF FULLY IN THE STORY YOU’RE TELLING

W. Eugene Smith believed that photography was not just a job—it was a moral and emotional contract with the truth. Unlike photojournalists who dropped in and out of scenes, Smith embedded himself deeply in the environments and lives of his subjects. For him, telling a story meant living it. His first lesson to emerging photographers is to fully immerse yourself in the world you are documenting. Because only by truly understanding it can you begin to tell its truth.

This was not metaphorical. Smith physically, emotionally, and even financially immersed himself in his stories. When he documented the effects of mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan, he lived among the victims for three years. He became part of their daily life, earning their trust, witnessing their struggles, and ultimately, telling their story with a gravity that no outsider could replicate.

Why Immersion Matters

Smith’s belief was simple but radical: superficial observation breeds superficial results. He argued that you cannot grasp the complexities, subtleties, and emotional weight of a story by simply observing from a distance. Immersion allows you to see not just what is happening, but why it’s happening. It lets you feel the rhythm of a place, the hopes and sorrows of its people, and the undercurrents that give a story its meaning.

When Smith photographed a country doctor in rural Colorado, he didn’t just shadow the man for a day. He lived with him, traveled with him, watched him perform surgeries, deliver babies, and grieve lost patients. The resulting images weren’t just pictures of a man—they were a meditation on vocation, compassion, and endurance.

Immersion Builds Trust

Subjects can tell when a photographer is just passing through. Real immersion builds trust. Smith’s long-term commitment to his subjects allowed him to capture moments of raw vulnerability. People let down their guard when they feel seen—not just looked at. Smith earned that privilege by showing up every day, asking questions, listening, and, most importantly, being present.

He did not treat people as subjects; he treated them as co-authors of the narrative. This respect translated into portraits that are tender, complex, and utterly human.

The Physical and Emotional Cost of Immersion

Smith paid a price for his immersive approach. The emotional toll of living with people in pain, injustice, or despair was enormous. He often pushed himself to exhaustion, financially ruined himself for projects, and even jeopardized his health. In Minamata, he was physically attacked by corporate goons trying to silence the story. But Smith never backed away.

His philosophy was that truth was worth suffering for. He saw photography not as self-expression, but as self-sacrifice in the service of others. This is a sobering but powerful message for young photographers: storytelling is not always comfortable. It demands courage.

Lessons for Contemporary Photographers

Today, in the age of rapid-fire content and algorithm-driven visual culture, Smith’s method might seem like a relic. But in truth, it’s more relevant than ever. Audiences are starved for authenticity. True immersion is a way to rise above noise and reconnect photography with its highest purpose: understanding.

Practical ways to practice immersive storytelling include:

- Spend extended time with your subjects before even taking a photograph.

- Research deeply. Understand the history, politics, and human context.

- Be patient. Let the story unfold naturally rather than imposing your narrative.

- Accept that immersion is emotionally taxing—and prepare for that.

- Don’t aim to capture everything. Aim to capture what matters most.

Case Study: Minamata

Smith’s documentation of mercury poisoning victims in Minamata remains one of the most haunting photographic essays ever published. His image of a mother bathing her severely deformed daughter is almost religious in its intimacy and tenderness. It wasn’t just a photograph—it was an indictment, a prayer, and a call to action.

The reason it struck such a deep chord is because Smith was not a tourist in that tragedy. He lived it. That photo wasn’t captured—it was earned.

Philosophical Reflection: To immerse is to respect. Smith teaches us that only by surrendering our distance can we truly understand another’s life.

Life Reflection: In life, as in photography, transformation requires immersion. You cannot skim the surface and expect depth. Whether you’re building relationships, chasing dreams, or telling stories—go all in.

Quote: “Passion is in all great searches and is necessary to all creative endeavors.” — W. Eugene Smith

2. PHOTOGRAPHY IS A FORM OF ADVOCACY—USE IT TO SPEAK FOR THOSE WHO CAN’T

For W. Eugene Smith, the camera was never a passive observer—it was a powerful tool for change. His images did not merely document—they confronted, provoked, and bore witness to injustice. Smith’s second lesson is a moral imperative: photography must have a voice, and that voice must speak for those who are silenced, ignored, or oppressed.

From the beginning of his career, Smith’s work was infused with a sense of ethical urgency. He saw photography as a form of social action—a way to illuminate suffering, expose wrongs, and force viewers to confront realities they might otherwise ignore. His work at Life magazine and later independent essays reflected a deep commitment to visual advocacy.

Minamata as Visual Protest

Smith’s most famous advocacy project was his essay on Minamata disease, a neurological syndrome caused by mercury poisoning from corporate pollution. Smith did not just photograph the victims—he made the viewer feel their pain. The now-iconic image of Tomoko Uemura being bathed by her mother became a global symbol of environmental injustice.

But Smith’s advocacy didn’t stop at imagery. He used captions, text, exhibitions, and lectures to support his photographic message. He worked closely with activists and even risked his life to publish these images against powerful corporate resistance. For Smith, the photo was only the beginning. The real goal was impact.

The Role of the Photographer as Witness

Smith understood that to bear witness is not a neutral act—it’s a responsibility. To photograph a suffering person is to enter into a moral relationship. He believed photographers had a duty not to aestheticize pain but to humanize it. His compositions, lighting, and framing were designed to evoke empathy, not pity; connection, not detachment.

He once said, “I’ve never made any picture, good or bad, without paying for it in emotional turmoil.”

Photography as a Weapon of Compassion

Smith’s lens was a weapon, but one loaded with compassion. His photo essay “Nurse Midwife” followed Maude Callen, a Black nurse caring for rural communities in the American South. At a time when institutionalized racism was deeply embedded in American healthcare, Smith’s story brought dignity and visibility to a forgotten hero.

As a result of the essay, readers raised over $20,000 in donations—enough to help build a clinic in Callen’s honor. Smith’s work didn’t just document suffering; it mobilized compassion into action.

Why This Lesson Matters Now

In today’s image-saturated world, it is easy to become desensitized. But Smith’s work reminds us that images still matter—if we make them matter. Advocacy through photography isn’t about going viral. It’s about being intentional. About standing with those who can’t stand alone.

Contemporary photographers have access to platforms Smith could never have imagined. But they also face ethical challenges he helped define: how do we represent pain without exploiting it? How do we advocate without appropriating?

Ethical Advocacy in Practice:

- Gain consent whenever possible.

- Understand the full context—don’t parachute into suffering.

- Collaborate with local voices and activists.

- Use captions and context to guide interpretation.

- Follow up—what happens to the subject after the image circulates?

Case Study: The Jazz Loft Project

While less overtly activist, Smith’s years documenting musicians at his Manhattan loft served as cultural preservation. He captured an era of creativity and struggle among Black jazz artists who had limited mainstream visibility. His lens uplifted their brilliance and documented their reality.

Smith’s advocacy extended beyond politics into the realm of human dignity. Whether photographing the dying, the poor, or the overlooked, he reminded the world that every human being deserves to be seen.

Philosophical Reflection: Photography is not just a mirror—it is a megaphone. Smith teaches us to amplify voices that power seeks to silence.

Life Reflection: In life, as in art, we are called to witness not from afar, but from beside. To stand with, to speak up, and to use our gifts to protect the dignity of others.

Quote: “I am constantly torn between the attitude of the conscientious observer and the desire to intervene. But I believe that if I do my job well enough, the picture will be the intervention.” — W. Eugene Smith

Discover the Spirit of COUNTRY AND RURAL LIFE

“Rustic simplicity captured in light, colour, and heartfelt emotion.”

Black & White Rural Scenes ➤ | Colour Countryside ➤ | Infrared Rural Landscapes ➤ | Minimalist Rural Life ➤

3. EMBRACE COMPLEXITY—THE TRUTH IS RARELY SIMPLE

W. Eugene Smith was a master at resisting the easy narrative. He understood, perhaps more deeply than any of his contemporaries, that truth in human experience is rarely linear, and never neat. His third lesson is a reminder to all emerging photographers: avoid simplification. Truth is nuanced, layered, and often contradictory. To photograph with integrity means to embrace the messiness of life.

Smith’s essays were not about illustrating an idea—they were about uncovering one. He approached each project with a journalist’s curiosity, a poet’s heart, and a philosopher’s mind. He questioned everything, edited relentlessly, and sought emotional and psychological depth far beyond what a single image could contain.

Why Complexity Matters in Storytelling

In a world that increasingly favors binary perspectives—good/bad, hero/villain, success/failure—Smith insisted on complexity. His photo essays often avoided tidy conclusions. They left viewers with questions instead of answers, inviting them to feel the weight of a situation rather than drawing a definitive moral line.

Consider his series “Spanish Village.” It’s one of Smith’s most celebrated photo essays, not because it offers dramatic action or political clarity, but because it captures the everyday rhythms, rituals, joys, and struggles of life in a remote postwar Spanish town. The images move between hardship and grace, youth and age, faith and fatigue.

Smith didn’t just photograph the poverty—he also photographed resilience. He didn’t just show work—he showed worship. By allowing contradictions to coexist in the narrative, he offered a deeper, more honest portrait of the village and its people.

Editing as an Act of Complexity

Smith’s darkroom and contact sheets were battlegrounds of emotional struggle. He often shot thousands of frames and spent months editing. He rearranged, recut, and reinterpreted images until they reflected not only the factual story but the emotional complexity of the lived experience.

He was obsessive not for vanity, but because he believed that every image contributed a layer to the overall truth. Editing, for Smith, was an act of sculpting—not in marble, but in ambiguity. It was about finding the precise balance of contradiction, compassion, and clarity.

Resisting Propaganda, Embracing Humanity

Smith was deeply wary of the ways photography could be used to manipulate. He had seen how propaganda, both governmental and commercial, stripped nuance from real life to serve political or ideological ends. He resisted this at every turn.

His photo essays refused to flatten people into symbols. Even when working for Life magazine, he battled editors who tried to impose simplified narratives. In fact, his artistic independence eventually led to professional clashes and financial strain—but he remained unwavering in his pursuit of authenticity.

Portraits That Hold Contradictions

One of Smith’s unique gifts was his ability to create portraits that held multitudes. His images could simultaneously convey strength and fragility, pride and grief, love and loss. He understood that the human face is not a headline—it’s a novel.

In his portrait of a coal miner’s daughter gazing through a cracked window, we don’t see a caricature of poverty—we see introspection, longing, a dream paused in shadow. It’s not a symbol—it’s a person.

The Danger of Easy Narratives

Smith’s work is a reminder that easy narratives are seductive but often dishonest. They reduce individuals to issues, communities to problems, and lives to statistics. The responsibility of the photographer is not to simplify, but to illuminate.

Photographers must resist the urge to create emotional shortcuts. This means acknowledging when a story doesn’t have a hero, when suffering is accompanied by joy, and when solutions are far more complex than causes. It means trusting your audience to grapple with ambiguity—and yourself to live in it.

Practical Ways to Embrace Complexity in Photography:

- Photograph the in-between moments, not just the peaks or valleys.

- Include context in your compositions—don’t crop out the contradictions.

- Pair images that reveal different sides of the same person or situation.

- Avoid over-editing emotional content. Let discomfort sit alongside beauty.

- Talk to your subjects—listen to how they define themselves.

Case Study: Pittsburgh Project

In the late 1950s, Smith embarked on a massive photographic essay documenting Pittsburgh. What was intended to be a few weeks turned into a multi-year obsession. He shot over 17,000 images in an attempt to portray the industrial, cultural, and spiritual complexity of the city.

Though the project was never fully published in his lifetime, it remains one of the most ambitious photographic endeavors of the 20th century. The images ranged from jazz clubs to steel mills, from children to religious ceremonies. Together, they created a mosaic that defied any single interpretation.

Philosophical Reflection: Truth is not a headline—it is a conversation. Smith teaches us that the best stories are not told in black and white, but in the infinite shades between.

Life Reflection: In life, too, we must learn to live with contradictions. People are rarely only what they seem. Growth, grief, and grace often coexist. Embrace complexity, and you begin to see more clearly.

Quote: “What use is having a great depth of field if there is not an adequate depth of feeling?” — W. Eugene Smith

4. LET YOUR EMOTIONS GUIDE YOUR CAMERA—FEEL FIRST, THEN SHOOT

For W. Eugene Smith, photography was not a cold, objective act. It was an emotional pilgrimage. He believed that to create meaningful images, a photographer must first feel deeply. Emotions weren’t obstacles—they were the essence of truth. His fourth lesson is for every photographer who has ever questioned whether it’s okay to get involved: don’t just observe—empathize. Let your feelings be the lens before your camera.

Smith rejected the notion of emotional detachment in journalism. He was not a dispassionate recorder of events—he was a soul tethered to every frame he took. His images bleed with feeling because they were created through vulnerability, not distance. And he paid for this artistic honesty with years of emotional exhaustion, financial hardship, and profound personal sacrifice.

Why Emotion Matters in Photography

Photography, for Smith, was not merely about composition or lighting. It was about emotional fidelity. He once said, “The photograph is a small voice, at best, but sometimes—just sometimes—one photograph or a group of them can lure our senses into awareness.”

His goal was never simply to show—it was to make you feel. His pictures do not lecture; they ache. Whether it’s a soldier dying on a battlefield or a mother bathing her deformed daughter, the power of the image lies not in its aesthetics, but in the emotion it carries.

Emotional Risk-Taking

Smith was willing to put himself at emotional risk to get close to his subjects. He lived through the griefs they endured. He cried with them, raged with them, broke with them. His immersion in Minamata was not just physical—it was emotional. He allowed their sorrow to become his own. He did not hide behind his camera. He leaned in.

This emotional vulnerability allowed him to take photographs that pierce the viewer. His Minamata series would not have worked if he had maintained professional distance. The quiet reverence in his photograph of Tomoko and her mother is not something that can be directed—it must be felt, deeply.

Feeling First, Then Framing

Smith did not click the shutter at every opportunity. He waited until the emotional tone felt right. He knew that the best moments were not necessarily the most dramatic—but the most honest. He composed from the gut, not just the eye.

In his photo essay “Country Doctor,” the moments that stay with the viewer are not surgeries or emergencies—they are moments of fatigue, solitude, tenderness. A doctor leaning against a wall. A hand on a child’s forehead. These are not flashy moments—they are felt ones.

Teaching Yourself to Feel

Smith believed that the technical side of photography could be taught. What couldn’t be taught—only cultivated—was emotional acuity. This required silence. Presence. The ability to pause long enough to feel the tension in a room, the sadness behind a smile, the strength behind frailty.

To become a photographer who feels first is to become a person who listens deeply. This is not just good advice for photography—it’s a way of being.

Practical Ways to Let Emotion Guide Your Work:

- Before lifting your camera, ask: what am I feeling right now?

- Let a moment settle before photographing it. Breathe with it.

- Study your own emotional responses to people and places. Let them guide your focus.

- Review your images with emotion in mind: which ones feel true, not just well-composed?

- Avoid over-shooting. Wait for the moment that hits you in the gut.

Case Study: World War II Photography

Smith’s combat photography is some of the most harrowing ever produced. But its strength comes not from the horror it depicts—but from the humanity it refuses to surrender. His images from Saipan and Okinawa are haunted not by gore, but by grief. A dying soldier. A medic holding a comrade. These were not trophies—they were eulogies.

Smith was injured by mortar fire while on assignment, nearly losing his life. That injury didn’t stop him. It made him more committed. His emotional pain became his moral compass.

Philosophical Reflection: To feel is to see. Smith teaches us that emotion is not the opposite of objectivity—it is the foundation of truth.

Life Reflection: In life, as in art, we often guard ourselves from feeling too much. But to live fully, we must risk feeling deeply. That risk is where meaning lives.

Quote: “I am an incurable emotionalist. That is why I believe in photojournalism.” — W. Eugene Smith

5. MASTER TECHNIQUE TO SERVE, NOT SUPPRESS, YOUR VISION

W. Eugene Smith was a technical perfectionist—not for the sake of showing off, but because he believed every photographic choice should serve emotional truth. His fifth lesson reminds photographers that technique is not the destination—it is the road. Master it not to dominate your art, but to free it.

Smith worked obsessively in the darkroom. He would spend hours—sometimes days—dodging, burning, cropping, and printing a single image until it fully matched the feeling he had when he pressed the shutter. To him, a technically perfect image that failed to convey truth was a failure. Conversely, a slightly imperfect shot that conveyed honest emotion was a triumph.

Why Technique Matters

In Smith’s words, “I try to take what voice I have and give it to those who don’t have one.” For this voice to be heard clearly, the image had to be crafted carefully. Smith knew that exposure, composition, timing, contrast, and development were all part of storytelling.

If an image was too dark, it might lose meaning. If it lacked tonal range, it might fail to evoke mood. Technique was not about style or precision for its own sake—it was about impact.

The Darkroom as an Extension of Emotion

Smith’s darkroom was a sacred space. He believed printing was as important as shooting. He often reworked negatives years after they were taken. His darkroom techniques became legendary for their intensity and detail. For the photograph of the Spanish wake in “Spanish Village,” he worked for days adjusting contrast and shadow until the grief in the room could be felt as much as seen.

He approached printing the way a composer approaches a score—carefully, intuitively, and with reverence.

Learning the Rules to Break Them

Smith knew all the traditional rules of photography—and he broke them when necessary. He wasn’t afraid of grain. He used blur when it conveyed motion or emotion. He embraced deep shadows when they told part of the story.

But these were intentional choices, not mistakes. That’s the difference. Smith believed that only by fully mastering photographic tools could you know when to put them aside.

Mastery Is Not the Same as Control

Many photographers confuse mastery with control. For Smith, mastery meant flexibility. It meant knowing how to bend light, time exposure, and alter depth of field to suit the narrative needs of a moment.

In his essay on Maude Callen, the nurse-midwife, Smith used lighting that gently caressed her face, creating a maternal halo. In his war photos, he let contrast and grit dominate, underscoring chaos. Technique served message.

Practical Approaches to Technical Mastery

- Study the technical side of your craft. Know your tools inside and out.

- Practice under different lighting, weather, and motion conditions.

- Learn traditional printing methods—even if you shoot digital.

- Revisit your images in post-production with fresh emotional perspective.

- Analyze Smith’s work and reverse-engineer his decisions: why this exposure? Why that crop?

Case Study: Spanish Village

This photo essay remains a masterclass in technique-as-service. Smith adjusted not only exposure and composition, but the sequencing of the images to create a narrative arc. He took mundane details—a funeral procession, children playing, a priest preparing communion—and elevated them into a visual symphony.

His framing was never random. His depth of field was intentional. The spacing of light and dark frames created rhythm and emotional contrast.

Philosophical Reflection: Art must be free—but freedom requires structure. Smith teaches that technical mastery gives the artist more room to speak with clarity.

Life Reflection: In life, as in art, knowing the tools is not enough. Wisdom lies in knowing when and how to use them—and when to let feeling override formula.

Quote: “Technique isn’t the goal. It’s the language. Learn it well, so your soul can speak clearly.” — Inspired by the spirit of W. Eugene Smith

Immerse in the MYSTICAL WORLD of Trees and Woodlands

“Whispering forests and sacred groves: timeless nature’s embrace.”

Colour Woodland ➤ | Black & White Woodland ➤ | Infrared Woodland ➤ | Minimalist Woodland ➤

6. DEFY DEADLINES IF THEY COMPROMISE THE TRUTH

W. Eugene Smith famously waged war against editorial deadlines when they interfered with the integrity of a story. He was notorious for blowing past publishing dates—not out of arrogance, but out of reverence for the subject. His sixth lesson for photographers is both practical and philosophical: never let speed take priority over substance.

Smith’s struggle with magazine editors at Life is legendary. His perfectionism, combined wit

h his need to get everything right, made him nearly impossible to manage. But behind the missed deadlines and prolonged photo essays was a deep commitment to ethical representation. He believed a photograph was not finished until it did justice to the truth it aimed to reveal.

The Conflict Between Journalism and Justice

Smith understood the business side of publishing, but he rejected the commodification of stories. To him, people’s lives weren’t content. They were sacred narratives. When a deadline threatened to reduce the complexity of a story, he fought back—sometimes walking away from assignments entirely.

His essay on the city of Pittsburgh was supposed to be a two-month commission. It turned into a years-long odyssey involving over 17,000 negatives. Though the project strained his finances and relationships, it became one of the most ambitious photographic undertakings of the 20th century.

Why This Matters Now More Than Ever

In an era of social media algorithms and real-time publishing, there’s immense pressure to be quick. Photographers today often have minutes, not months, to post, publish, or respond. But Smith’s career is a reminder that lasting work takes time.

Speed prioritizes what is sensational. Time prioritizes what is substantial. The former disappears in a scroll; the latter endures in hearts and archives.

The Cost of Artistic Integrity

Smith paid a steep price for his refusal to rush. He burned bridges with editors, lost contracts, and became known as “difficult.” But his best work—Minamata, Spanish Village, Country Doctor—would not exist without that stubborn insistence on time.

His legacy proves that it is better to be difficult in the service of truth than easy in the service of convenience.

Balancing Practical Realities with Ethical Demands

Smith was not naïve. He knew that artists need to earn a living. But he also believed that compromising the core of one’s message for the sake of expediency made the entire endeavor hollow.

He often supplemented his work through commercial jobs, then funneled that income back into long-term personal projects. This model—creative bifurcation—allowed him to protect the sanctity of his photo essays.

Advice for Photographers Facing Deadline Pressure:

- Negotiate deadlines with clarity about your process.

- Build a financial buffer to support longer-term work.

- Partner with publications that value quality over quantity.

- Use fast work to fund slow art.

- Don’t be afraid to delay if the story demands more time.

Case Study: Minamata Delay

Smith’s delay in completing the Minamata project stemmed from both logistical and ethical reasons. He refused to photograph staged scenes, insisted on full contextual accuracy, and spent time healing after being physically attacked while working on the project.

The delay frustrated publishers. But when the essay was finally published, it became one of the most powerful environmental justice stories ever told.

Philosophical Reflection: Deadlines are human inventions. Truth is not. Smith teaches us that honoring the story is more important than meeting the schedule.

Life Reflection: In life, too, we are pressured to rush—toward decisions, judgments, goals. But the most important things—growth, understanding, connection—require time. Don’t rush the becoming.

Quote: “Hard is the artist who is expected to produce for deadline; harder still is the truth that will not arrive on schedule.” — Inspired by the spirit of W. Eugene Smith

7. DON’T SHOOT FOR PRAISE—SHOOT TO MAKE PEOPLE FEEL SOMETHING

W. Eugene Smith never sought applause. He sought understanding. His seventh lesson to photographers is this: don’t shoot for recognition—shoot to evoke feeling. His most famous images are not celebrated for their perfection but for their power. They do not decorate—they disarm.

From the anguished look of a soldier in the Pacific to the serene dignity of a mother in Minamata, Smith’s photographs were not about showcasing his skill. They were about stirring something deep in the viewer. He wanted people to feel what he felt when he stood behind the lens: outrage, reverence, grief, awe.

Why Intention Matters More Than Applause

In today’s culture of instant feedback, it’s easy to be tempted by the dopamine hit of likes, shares, or awards. But Smith’s career reminds us that the most important work often goes unrecognized—at least for a while. He was dismissed, criticized, even abandoned by major institutions because of his stubborn ethics and slow pace.

But over time, his body of work endured—not because it was fashionable, but because it was felt.

Emotional Impact Over Technical Brilliance

Smith was a master technician, but he never let technique outshine emotion. He often selected imperfect frames if they carried more feeling. His images weren’t flawless—they were human. Slight blurs, messy backgrounds, or irregular compositions never disqualified a photo if the emotional truth was strong enough.

He believed the photographer’s job was not to impress, but to connect. And connection requires vulnerability.

Photographing With a Sense of Purpose

Smith carried a sense of moral urgency into his work. He didn’t document events to fill space—he did it to change hearts. Whether it was his essay on Albert Schweitzer in Africa or the forgotten laborers of Pittsburgh, Smith shot with a message in mind.

That message wasn’t always stated—it was felt. His work had what musicians call tone. It left a vibration in the chest, an aftertaste in the spirit.

Praise Is Temporary. Resonance Is Timeless.

Many of Smith’s greatest achievements were unheralded in his lifetime. He lived in poverty, battled editors, and was often misunderstood. But his images found their way—quietly, persistently—into textbooks, museums, and the hearts of those who cared.

His life reminds us that the work that moves people isn’t always the work that wins prizes.

Advice for Photographers Craving Recognition:

- Ask yourself why you’re picking up the camera. What do you need to say?

- Focus on the emotion in the frame, not just the perfection.

- Create work that you’re proud of, even if no one notices it immediately.

- Don’t chase trends—chase truth.

- Trust that real impact often happens slowly and invisibly.

Case Study: Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath

Smith’s photograph of Tomoko Uemura is one of the most haunting images ever made. It didn’t win a Pulitzer. It wasn’t widely circulated at first. But over time, it became the soul of the Minamata story.

It evokes compassion, outrage, sorrow, and tenderness—all at once. And it does so without needing a caption. That’s the power of an image made with feeling, not for approval.

Philosophical Reflection: Applause fades. But impact echoes. Smith teaches us to work for the soul, not the spotlight.

Life Reflection: In life, too, our best moments are often the quiet ones. The acts of love, courage, and truth that no one sees—but that change everything.

Quote: “Let truth be your applause. Let feeling be your focus. The rest will come—or not. But your work will still matter.” — Inspired by the spirit of W. Eugene Smith

8. LIVE YOUR MESSAGE—LET YOUR LIFE REFLECT YOUR LENS

For W. Eugene Smith, the camera was an extension of conscience, and photography was not merely a profession—it was a way of being. His eighth lesson is simple yet profound: your work must be consistent with your life. To photograph truthfully, you must live truthfully.

Smith’s life was notoriously difficult—fraught with personal sacrifice, mental and physical illness, broken relationships, and financial hardship. But he never separated the man from the mission. His photographs were infused with the same moral fire that guided his decisions outside the frame.

He didn’t just show injustice—he refused to participate in it. He didn’t just photograph compassion—he extended it to those around him. His life and lens were one.

Why Consistency Matters

Photographers often focus on external stories, forgetting that their personal ethics shape their images more than any lens ever could. Smith understood that dishonesty, even in one’s personal life, could distort perception.

He was brutally honest—not only with his subjects, but with himself. This honesty gave his work integrity. Audiences trusted his images because they could sense they were made by someone who meant every frame.

Living With Purpose

Smith turned down lucrative jobs that conflicted with his values. He lived simply, often in self-imposed poverty, so that he could pursue long-form projects with complete freedom. This wasn’t romanticized suffering—it was conviction in action.

Even in his chaotic Jazz Loft years, where he obsessively recorded and photographed musicians and street life from a New York apartment, his mission was clear: document life unfiltered, unpolished, unguarded.

When Your Life and Work Are Aligned, They Reinforce Each Other

Smith’s depth as a photographer came from his depth as a human being. He didn’t use photography to escape life—he used it to engage more deeply with it. His camera was always in service to his beliefs.

He saw his camera as a tool of communion—not exploitation. And that perspective changed everything about how he worked: how he approached people, what he noticed, what he chose to include or exclude.

The Risks of Living the Message

Living your message, as Smith did, is not easy. It invites discomfort. It demands discipline. It may even cost you jobs or friends. Smith’s insistence on creative and ethical independence made him a pariah in some professional circles.

But it also made him a legend.

When photographers compromise their values, it shows—in the work and in the soul. Smith’s life offers an alternative: embody the message, and even if the work takes longer or reaches fewer people, it will matter.

Advice for Living the Message:

- Know what you stand for—and let that guide what you shoot.

- Let your compassion off-camera match the compassion in your images.

- Turn down work that contradicts your deepest beliefs.

- Pursue long-term projects even if they bring no immediate reward.

- Understand that your life is your portfolio, too.

Case Study: Leaving LIFE Magazine

Smith’s departure from Life was both principled and painful. He grew disillusioned with editorial control and resisted the magazine’s tendency to sanitize or simplify complex stories.

Rather than stay and compromise, he walked away—choosing artistic exile over ethical dilution. He paid for that decision with obscurity and struggle. But it also gave him the freedom to pursue the Minamata project, which would define his legacy.

Philosophical Reflection: The image is a mirror. If your soul is fogged with compromise, the reflection will be unclear. Smith teaches us to clean that mirror with honesty.

Life Reflection: In life, as in photography, integrity is the invisible light source. It sharpens everything. Live your message, and the world will feel it—even if they never see your face.

Quote: “Live the story you want to tell. Then your lens will always speak the truth.” — Inspired by the spirit of W. Eugene Smith

Journey into the ETHERAL BEAUTY of Mountains and Volcanoes

“Ancient forces shaped by time and elemental majesty.”

Black & White Mountains ➤ | Colour Mountain Scenes ➤ |

9. NEVER UNDERESTIMATE THE POWER OF A SINGLE IMAGE

Smith’s ninth lesson urges photographers to remember the singular force a single image can carry. While he was known for complex essays and immersive series, Smith also revered the standalone photograph—a frame that could communicate an entire story, collapse time, and ignite social change.

The photograph, for Smith, was not just a document. It was a declaration. One image—honest, emotionally resonant, and ethically crafted—could shake public opinion, stir moral reflection, and echo through history.

Why the Single Image Still Matters

In an era of visual overload, we risk forgetting the potency of one moment caught in time. We scroll past hundreds of images a day. But every once in a while, one frame stops us cold. It says something we didn’t know we needed to hear. It becomes unforgettable.

Smith believed deeply in the ability of such images to become cultural touchstones. Think of Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” or Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl.” Smith aimed for that kind of clarity—not as spectacle, but as moral insight.

Creating the Iconic: Simplicity, Emotion, and Timing

Smith’s most famous standalone image—Tomoko Uemura in her bath—was not cluttered with context. It didn’t need an essay beside it. The moment, gently captured with reverence and intimacy, was the story.

He knew that to create such an image, the photographer must know when not to shoot, when to wait, when to witness. Timing was everything. Not in the mechanical sense, but in the emotional one.

The Single Image as Catalyst

When Life magazine published Smith’s image from Minamata, the world took notice. The Japanese government was pressured. Chisso Corporation faced renewed scrutiny. Environmental journalism found a new standard.

One image became an outcry, a lament, a prayer.

Smith understood that sometimes, one frame could do what ten thousand words could not. It bypassed logic and entered the heart.

Editing as Respect

Part of honoring the single image, for Smith, was editing with intention. He did not throw every frame into the world. He chose what mattered most—what held the deepest emotional charge.

This discipline is lost in many modern practices. Smith teaches us that it’s not about how many images we make—it’s about how many truly mean something.

Advice for Crafting the Singularly Powerful Image:

- Wait for the moment that moves you before you move the shutter.

- Compose with clarity. Don’t overcrowd your frame.

- Avoid gimmicks. Truth doesn’t need adornment.

- Ask yourself: if this were the only image the world saw from this moment, would it matter?

- Trust quiet moments. Stillness can be louder than action.

Case Study: The Dying Marine

Smith’s harrowing photograph of an injured marine in the Pacific captures pain, bravery, and mortality in one haunted expression. You don’t need to know the backstory. You feel it.

That image has haunted generations—not with shock, but with soul. It reminds us that sometimes one face is enough to tell the whole war.

Philosophical Reflection: In the rush of storytelling, don’t forget the sentence that stands alone. One image, well-made, can speak a lifetime.

Life Reflection: In life, too, there are single moments that define us. Not always the loudest. Often the quietest. Smith teaches us to honor those moments—with our lens, and our lives.

Quote: “Let one image do what a thousand could not. Not because it says more, but because it says what matters.” — Inspired by the spirit of W. Eugene Smith

10. TELL THE STORIES OTHERS WON’T—EVEN IF IT COSTS YOU

W. Eugene Smith’s work was not safe. He never stayed in the comfort zones of popular assignments or stories with easy answers. Lesson ten is a challenge: go where others won’t, tell what others won’t tell—even if it isolates you. The truth rarely lives where it’s convenient.

Smith sought out stories that institutions ignored or actively silenced. He turned his lens toward the hidden, the uncomfortable, and the painful. From war injuries and systemic poverty to environmental poisoning and racial inequity, Smith’s photography exposed wounds society would rather keep bandaged.

Why Dangerous Stories Matter

The stories that carry the most transformative power are often the ones people don’t want told. They unsettle the status quo. They ask us to take responsibility. Smith knew that if photographers avoid the hard stories, we collectively fail to confront the injustices in front of us.

He believed that the most important thing a photographer can do is illuminate darkness—not for shock, but for healing.

The Cost of Courage

Smith’s Minamata project came at great personal cost. He was physically attacked by employees of the Chisso Corporation. He suffered permanent injuries. But he refused to stop. Because to Smith, silence in the face of injustice was not neutrality—it was complicity.

He was not reckless. He was resolute. He weighed the risks, and still chose to stand on the side of truth.

You May Lose Opportunities—But You’ll Keep Integrity

Smith’s insistence on truth-telling cost him clients, friends, and financial security. But he never lost himself. He never became a pawn for propaganda. In a world that constantly pressures creatives to sell out, Smith held the line.

He understood that one image made with courage is worth more than a thousand made with compromise.

Why Most People Avoid These Stories

The difficult stories take time. They invite criticism. They trigger emotional distress. They might not “sell.” Smith knew all of this. And still, he leaned in.

He didn’t believe in neutrality for its own sake. He believed in choosing sides—the side of the suffering, the silenced, the truth.

Advice for Photographers Seeking to Tell Dangerous Stories:

- Protect yourself, but don’t protect your comfort.

- Seek out voices that are usually ignored.

- Prepare for resistance—legal, social, emotional.