Diane Arbus: Unmasking Truth in Unusual Portraits

Table of Contents

-

Short Biography

-

Type of Photographer

-

Key Strengths as Photographer

-

Early Career and Influences

-

Genre and Type of Photography

-

Photography Techniques Used

-

Artistic Intent and Meaning

-

Visual or Photographer’s Style

-

Breaking into the Art Market

-

Why Photography Works Are So Valuable

-

Art and Photography Collector and Institutional Appeal

-

Top-Selling Works, Major Exhibitions and Buyers (with current resale values)

-

Lessons for Aspiring, Emerging Photographers

-

References

Get to Know the Creative Force Behind the Gallery

About the Artist ➤ “Step into the world of Dr. Zenaidy Castro — where vision and passion breathe life into every masterpiece”

Dr Zenaidy Castro’s Poetry ➤ "Tender verses celebrating the bond between humans and their beloved pets”

Creative Evolution ➤ “The art of healing smiles — where science meets compassion and craft”

The Globetrotting Dentist & photographer ➤ “From spark to masterpiece — the unfolding journey of artistic transformation”

Blog ➤ “Stories, insights, and inspirations — a journey through art, life, and creative musings”

As a Pet mum and Creation of Pet Legacy ➤ “Honoring the silent companions — a timeless tribute to furry souls and their gentle spirits”

Pet Poem ➤ “Words woven from the heart — poetry that dances with the whispers of the soul”

As a Dentist ➤ “Adventures in healing and capturing beauty — a life lived between smiles and lenses”

Cosmetic Dentistry ➤ “Sculpting confidence with every smile — artistry in dental elegance”

Founder of Vogue Smiles Melbourne ➤ “Where glamour meets precision — crafting smiles worthy of the spotlight”

Unveil the Story Behind Heart & Soul Whisperer

The Making of HSW ➤ “Journey into the heart’s creation — where vision, spirit, and artistry converge to birth a masterpiece”

The Muse ➤ “The whispering spark that ignites creation — inspiration drawn from the unseen and the divine”

The Sacred Evolution of Art Gallery ➤ “A spiritual voyage of growth and transformation — art that transcends time and space”

Unique Art Gallery ➤ “A sanctuary of rare visions — where each piece tells a story unlike any other”

1. SHORT BIOGRAPHY

Diane Arbus was born Diane Nemerov on March 14, 1923, in New York City, into a wealthy Jewish family who owned Russek’s, a prestigious Fifth Avenue department store. Raised in affluence but marked by an undercurrent of personal and emotional instability, Arbus developed an early interest in art, literature, and observation—tools she would later harness in her radical photographic practice.

She married Allan Arbus at age 18, and the couple soon began working in commercial fashion photography. Diane styled and conceptualized while Allan operated the camera. Though commercially successful, the fashion world left Diane feeling unfulfilled. By the mid-1950s, she began to pursue photography independently, attending classes with legendary street photographer Lisette Model at the New School. Model became a formative mentor, encouraging Arbus to dig deeper into her own sensibility and seek subjects that resonated with her complex inner life.

Arbus broke from convention by focusing on individuals and communities often unseen—or deliberately ignored—by mainstream society. Her portraits featured transgender people, nudists, dwarfs, carnival performers, people with intellectual disabilities, and eccentric middle-class New Yorkers. Rather than framing these individuals as curiosities, Arbus sought to portray them with unsettling intimacy and psychological honesty.

Her distinctive, uncompromising approach to photography soon gained attention in the art world. Her works were featured in Esquire and Harper’s Bazaar, and her inclusion in John Szarkowski’s pivotal 1967 MoMA exhibition New Documents solidified her place in the emerging canon of modern photography.

Behind her success, however, Arbus struggled with profound emotional turmoil. She suffered from depression and feelings of alienation throughout her life. Tragically, she took her own life on July 26, 1971, at the age of 48.

After her death, her work gained further prominence. A major retrospective at MoMA in 1972 and the posthumous publication of the monograph Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph introduced her to a global audience. Today, her photographs are regarded as among the most provocative and powerful in the history of portraiture, challenging viewers to reconsider assumptions about beauty, normality, and identity.

2. TYPE OF PHOTOGRAPHER

Diane Arbus is best described as a portrait photographer of the marginalized, a visual ethnographer of emotional and social fringes. She worked at the intersection of documentary photography, psychological portraiture, and conceptual art, using the camera to probe the invisible borders between the accepted and the excluded.

Unlike her contemporaries who leaned into street photography, abstraction, or idealized humanism, Arbus sought raw emotional authenticity. She was not interested in merely documenting how people looked but rather how they felt, how they inhabited their identities, and how they were perceived by or isolated from the world around them.

Arbus did not consider herself a journalist or anthropologist. She was an artist who saw photography as a form of confession and confrontation. Her images—stark, detailed, often unnerving—invite viewers into a space of intimacy that challenges comfort zones. She believed in looking directly at what others turned away from.

She belongs to a rare type of photographer: one who redefined the rules of engagement between the photographer and the subject. Rather than remaining distant or invisible, she entered her subjects’ lives, often building long-term relationships. This gave her work a raw immediacy and unfiltered psychological charge rarely seen in traditional portraiture.

Moreover, her work is often classified as psychological realism. It is not concerned with flattery or aesthetics in the classical sense but with a visceral truth—a brutal honesty that demands emotional engagement. This type of photography, where subject and photographer confront each other with mutual vulnerability, has since influenced generations of portrait artists, conceptual photographers, and filmmakers.

3. KEY STRENGTHS AS PHOTOGRAPHER

Diane Arbus possessed a range of artistic strengths that made her one of the most distinctive and influential photographers of the 20th century. Her work continues to resonate due to its psychological force, stylistic clarity, and moral complexity.

1. Uncompromising Honesty

Perhaps her most defining strength was her refusal to sanitize reality. Arbus did not attempt to hide blemishes, awkwardness, or emotional discomfort. Instead, she highlighted them. She saw beauty in the stark, the unusual, and the so-called grotesque—not to exoticize or exploit, but to understand and reveal.

Her work redefined what was acceptable as art and as subject matter in photography. She pushed beyond the polished facade and into the uncanny, the strange, and the deeply human.

2. Intimacy with Subjects

Arbus cultivated relationships with her subjects, often returning to photograph the same individuals multiple times. Her portraits were not stolen moments but collaborative constructions of vulnerability. This depth of engagement enabled her to capture expressions and postures that reflected authentic psychological states.

Whether photographing a nudist couple in their living room or a child holding a toy grenade in Central Park, her portraits suggest a mutual tension between exposure and concealment—one that reveals both the subject and the photographer.

3. Breaking the “Normal” Frame

Arbus questioned and dismantled societal norms. She was drawn to people who defied conventional ideas of beauty, gender, ability, or behavior. Her work challenges the viewer to confront their own prejudices and perceptions, forcing us to look rather than glance.

In doing so, she not only gave visibility to marginalized communities but also reframed the conversation around what constitutes humanity, dignity, and worth.

4. Distinct Visual Voice

Arbus developed a visual language that is immediately recognizable—centered subjects, direct gaze, frontal framing, square format, and flat lighting. Her images often appear deceptively simple, but their compositional austerity enhances psychological depth. This stylistic consistency added to her authority as an artist.

She was among the first to master this aesthetic of “emotional neutrality” as a way to intensify viewer discomfort and introspection, a technique that has since become foundational in conceptual and fine art portraiture.

5. Use of Medium Format for Psychological Precision

Switching from 35mm to a Rolleiflex medium-format camera in the early 1960s was a pivotal move. The square format, along with the waist-level viewfinder, allowed Arbus to engage directly with subjects while framing the image precisely.

This technical shift enhanced the sense of intimacy and psychological clarity, enabling her to produce portraits with unprecedented stillness and focus—a quality that makes her work so haunting and powerful.

6. Moral Complexity

Arbus’s greatest strength may lie in the moral ambiguity of her images. They are open-ended, defying easy categorization. Viewers are often left questioning whether they are complicit in voyeurism, admiration, empathy, or discomfort.

This complexity forces a deeper engagement with both the image and oneself. It positions Arbus as not just a documentarian, but as a philosopher with a camera, confronting what it means to look, to see, and to be seen.

4. EARLY CAREER AND INFLUENCES

Diane Arbus’s evolution as a photographer cannot be understood without considering her early immersion in art, her complex emotional landscape, and her formal and informal training. Her career was not linear; it was marked by moments of doubt, transformation, and the growing realization that photography could serve as a profound tool for exploring identity, discomfort, and human diversity.

Early Life and Commercial Beginnings

Born into the affluence of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Diane Nemerov grew up surrounded by fashion, aesthetics, and high culture. Her parents’ luxury department store, Russek’s, sold furs and designer clothing—an environment filled with artifice and aspiration. This early exposure would later inform her fascination with appearance, performance, and what lies behind the mask of the everyday.

At 18, Diane married Allan Arbus, an aspiring actor and photographer. The couple collaborated as a commercial photography team, shooting for Vogue, Glamour, Harper’s Bazaar, and Seventeen during the 1940s and early 1950s. Diane handled much of the creative direction, styling, and conceptual work, while Allan executed the camera work.

Though the pair found success in the fashion industry, Diane felt alienated by its perfectionism and superficiality. Her disillusionment with commercial photography pushed her to seek an independent voice—one that would contrast radically with the polished imagery she helped produce in her early career.

Lisette Model and Photographic Mentorship

A pivotal turning point came in 1956 when Diane began studying with Lisette Model, a bold street photographer known for her unfiltered depictions of people on the social periphery. Model became not only a teacher but a catalyst for transformation, encouraging Diane to develop her own visual language.

Model challenged Arbus to pursue honesty over beauty, to engage with difficult subject matter, and to abandon technical perfectionism in favor of emotional authenticity. Under her influence, Arbus moved away from 35mm photography and toward the Rolleiflex medium-format camera, which allowed for greater intimacy and technical clarity.

It was also through Model that Arbus gained exposure to European photography traditions, including August Sander’s typologies of German citizens and Weegee’s gritty New York crime scenes. These influences steered Arbus toward an approach that was both documentary and psychologically penetrating.

Shift Toward Personal Projects

In the late 1950s, Arbus began photographing independently, often walking the streets of New York alone and visiting unconventional locations: Times Square arcades, Coney Island, freak shows, and private clubs. Her subjects included drag queens, carnival performers, elderly eccentrics, and mentally disabled individuals, all of whom she approached with a mix of candor and empathy.

She immersed herself in these environments, often returning multiple times to build rapport. This process of sustained engagement allowed her to move beyond the surface and into the interior world of her subjects.

By the early 1960s, Arbus had fully abandoned commercial work to focus on her personal projects. She supported herself with magazine assignments and teaching, including courses at Parsons School of Design and Cooper Union. During this time, she also built relationships with other emerging photographers like Richard Avedon, Walker Evans, and Garry Winogrand.

Recognition and Institutional Support

Her breakthrough came in 1967 when John Szarkowski, director of photography at MoMA, included her work in the seminal exhibition New Documents alongside Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. This show marked the first major institutional recognition of her unique voice and heralded a new era of documentary photography focused on personal, social, and emotional reality.

Szarkowski wrote that Arbus was “interested in things as they are,” not as they ought to be. This curatorial endorsement placed her at the vanguard of a photographic shift—from aesthetics to psychological realism.

5. GENRE AND TYPE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Diane Arbus occupies a rare and singular position within the photographic genre. Her work doesn’t sit comfortably within any one classification but instead bridges several fields: fine art portraiture, psychological documentary, and conceptual realism. She explored the visual tensions between subject and viewer, fantasy and reality, normalcy and deviance.

Psychological Portraiture

Above all, Arbus’s photography is a study of the self—not only the subject’s, but the photographer’s and viewer’s. Her portraits convey an intense psychological weight, often confronting the camera with a directness that feels unfiltered and emotionally charged. This genre, sometimes referred to as “psychological portraiture,” centers on emotion, vulnerability, and identity over composition or setting.

She rejected the idea of the “decisive moment” in favor of prolonged presence, often encouraging her subjects to hold a pose or gaze steadily into the lens. The result is not a snapshot of life in motion, but a frame frozen in psychic time.

Documentary Work with a Twist

While Arbus’s work is often described as documentary, it differs radically from traditional social documentary photography. Rather than aiming to “inform” or inspire reform, her work resists moralization. She was not there to change the world—but to examine it, intimately and unflinchingly.

She chronicled America’s fringes without gloss or pity. In this way, she helped invent what would later be called “intimate documentary”—a blend of subjective inquiry and formal documentation that continues to influence contemporary photographers.

Fine Art Photography

Arbus was among the first to bridge the gap between documentary photography and fine art. Her work was widely exhibited in galleries and museums during her lifetime, culminating in a major posthumous retrospective at MoMA in 1972—the first solo show of photography ever held there.

Her images became part of a growing movement that saw photography not merely as reportage, but as personal vision and cultural critique, legitimizing the medium as high art.

Conceptual Realism

Arbus’s subjects often appeared as embodiments of societal archetypes—twins, giants, transvestites, nuns, socialites—but presented with a twist. By framing them in mundane or domestic contexts, she upended conventional narratives, pushing her work into the realm of conceptual realism.

This genre focuses on real people and situations but highlights their symbolic, psychological, or philosophical meanings. Arbus’s photographs were not constructed, but they revealed deep constructions of self, identity, and cultural alienation.

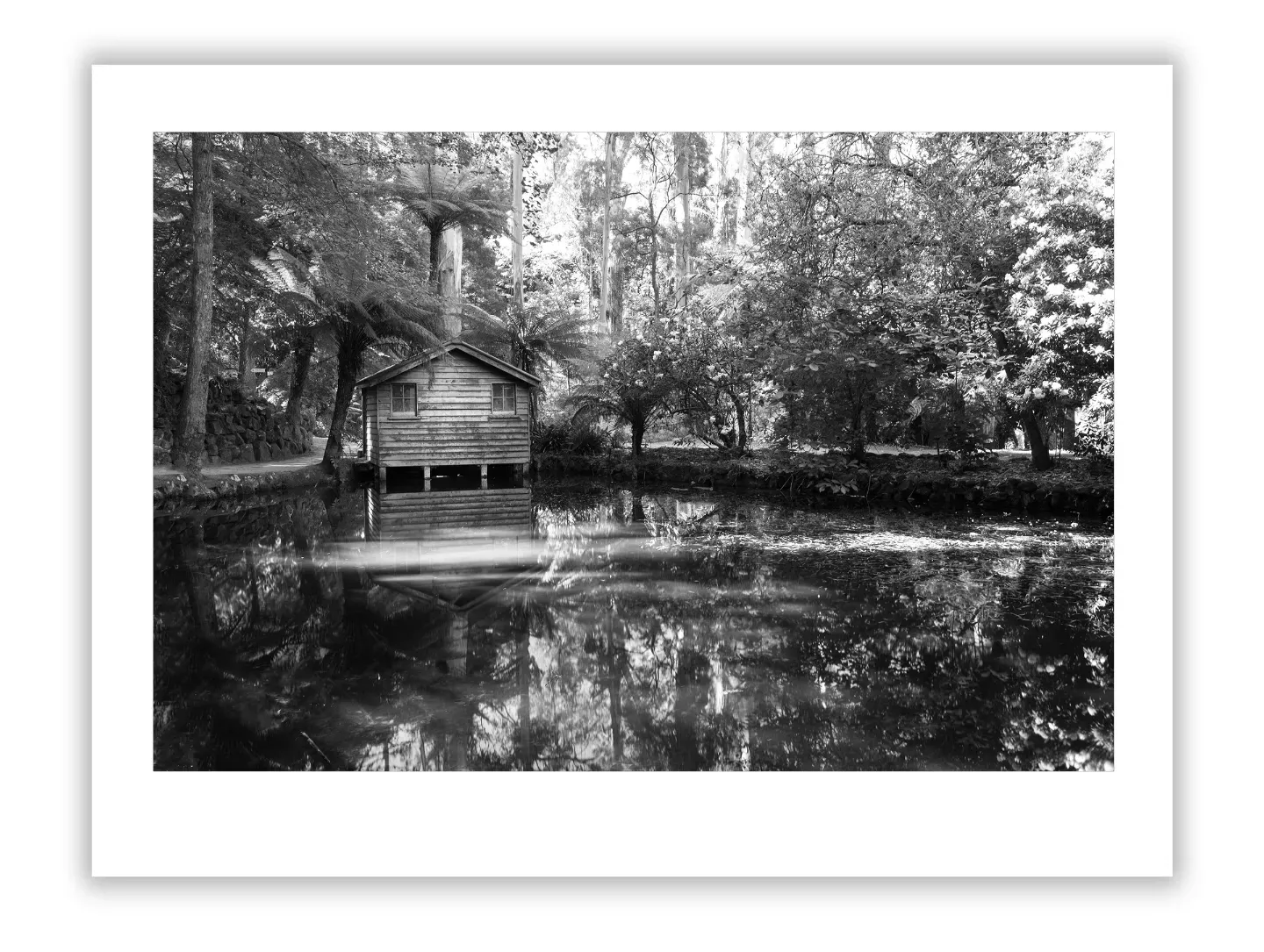

Explore Our WATERSCAPES Fine Art Collections

“Where water meets the soul — reflections of serenity and movement.”

Colour Waterscapes ➤ | Black & White Waterscapes ➤ | Infrared Waterscapes ➤ | Minimalist Waterscapes ➤

6. PHOTOGRAPHY TECHNIQUES USED

Diane Arbus’s technical methods were deceptively simple yet purposefully chosen to enhance the emotional and psychological depth of her work. Her shift from commercial fashion photography to intimate, emotionally raw portraiture was accompanied by major technical changes that became foundational to her style.

Medium Format Camera – The Rolleiflex

Arbus’s most defining technical decision was to adopt the Rolleiflex medium-format twin-lens reflex camera, which produced 6×6 cm square negatives. The camera’s waist-level viewfinder allowed Arbus to maintain direct eye contact with her subjects, creating a subtle intimacy absent in eye-level cameras.

This choice enhanced both clarity and stillness in her images. The Rolleiflex’s superior resolution brought out fine facial details—blemishes, wrinkles, skin texture—which aligned with Arbus’s ethos of emotional and physical honesty.

Square Format Composition

The square format removed directional bias (no vertical or horizontal dominance), allowing her to center her subjects with precision and authority. This visual symmetry gave her photographs a formal dignity and compositional stability, which contrasted with the emotional unease or social ambiguity within the frame.

Square format also intensified the viewer’s focus on the subject’s face and body, increasing the psychological weight of the image.

Direct Flash

Although she often used natural light, Arbus occasionally employed on-camera flash to flatten out the image and remove soft shadows. This created a confrontational, even clinical quality, stripping away glamour and emphasizing the realness of her subjects.

Her use of flash was not dramatic but functional—it created a sense of visual confrontation that placed the viewer and subject on equal, uncomfortable footing.

Front-Facing Framing

Most of Arbus’s portraits are shot straight-on, with the subject either centered or occupying a dominant position within the frame. This approach removed the photographer’s aesthetic distance and created a sense of psychological mutuality. It felt less like “looking at” and more like “being with.”

This frontal approach also demanded subject participation, reinforcing Arbus’s belief in collaborative vulnerability.

Natural Settings

Arbus photographed her subjects in their homes, neighborhoods, or personal spaces, favoring familiar environments over studio backdrops. This decision created more intimate portrayals, contextualizing subjects within their own worlds rather than isolating them as abstract forms.

Her attention to environment—sofa cushions, kitchen tiles, cluttered bedrooms—offered subtle commentary on class, lifestyle, and identity.

Minimal Manipulation

Arbus did not rely on darkroom trickery or post-production alteration. She preferred straight prints, often making only minor adjustments in contrast or exposure. Her goal was not aesthetic embellishment but emotional clarity.

She wanted the print to speak plainly, to confront the viewer with nothing but the subject and the tension between presence and perception.

7. ARTISTIC INTENT AND MEANING

Diane Arbus’s photography was driven by a deeply personal and unsettling artistic intent: to expose the emotional undercurrents of identity, deviance, and difference, and to confront the viewer with the complexity of looking. Her aim was not merely to document the unusual, but to transform the act of seeing into an act of feeling, often disturbing, sometimes tender, always raw.

A Radical Empathy

At the heart of Arbus’s intent was the notion of radical empathy. She immersed herself in the lives of people who were typically excluded from mainstream culture: trans people, circus performers, dwarfs, nudists, mentally disabled individuals, and everyday Americans whose lives didn’t conform to conventional ideals.

But Arbus did not see these individuals as “subjects.” She saw them as collaborators, co-creators in the photographic moment. Her work aimed to elevate the humanity of those whom society marginalized, while refusing to sentimentalize or beautify them.

Her intent was to show them as they were—with all their vulnerabilities and contradictions laid bare—asking the viewer to meet them face-to-face, without judgment or voyeurism.

The Space Between Viewer and Subject

Arbus was acutely aware of the ethical complexities of photography. Her images frequently invoke tension—not just between subject and photographer, but between subject and viewer. She understood that every photograph creates a power dynamic, and her work often plays with this tension deliberately.

Her portraits demand that we confront our own biases, discomforts, and curiosities. They ask not, “Who is this person?” but, “What is my reaction to this person, and what does that say about me?”

In this way, Arbus used photography to explore the very act of perception itself—how we look, why we look, and what we fail to see.

The Extraordinary Within the Ordinary

While many of her images depict people with extreme or non-conforming identities, Arbus was equally interested in the strangeness of the ordinary. Her famous photograph of an upper-class couple walking their dog in Central Park, or a suburban boy wearing a plastic Halloween mask, are examples of how she sought out the peculiar in the mundane.

To Arbus, everyone—no matter how “normal”—carried an undercurrent of weirdness, alienation, or hidden truth. She wanted to unmask this truth, to peel back the layers of social convention and reveal what lay beneath.

Discomfort as a Tool

Arbus did not shy away from making viewers uncomfortable. In fact, discomfort was one of her most powerful artistic tools. She believed that to truly see—to really look—was often to feel unsettled, and that photography had a moral duty to go beyond entertainment and into emotional confrontation.

Her photographs challenge the conventions of beauty, decency, and normalcy. By refusing to flinch, she created a new visual language that allowed the marginalized to speak for themselves, in their own stillness and presence.

A Mirror to the Self

Perhaps most profoundly, Arbus’s work is a mirror, not just a window. Her photographs are as much about the viewer as they are about the viewed. By asking us to look at “the other,” she forces us to see ourselves—not just in what we accept, but in what we deny.

She once said, “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.” This statement captures her intent precisely. Her work opens the door to mystery, but never fully lets us inside. It leaves us suspended in emotional ambiguity, and that is where its power lies.

8. VISUAL OR PHOTOGRAPHER’S STYLE

Diane Arbus’s visual style is as distinct and unmistakable as her choice of subjects. Her images are defined by their stark directness, psychological stillness, square format, and frontal composition—a style that confronts rather than flatters, and reveals rather than obscures.

The Square Format

Arbus’s choice to work almost exclusively with a 6×6 medium format (Rolleiflex) resulted in the square framing that became her visual signature. The square format brought an architectural and emotional balance to her compositions, creating a sense of symmetry and order that paradoxically emphasized the disorder or strangeness within the image.

Unlike rectangular formats, the square does not prioritize one orientation (landscape or portrait), allowing for a neutral, objective field where the subject confronts the viewer without hierarchy or distraction.

Centered and Frontal Framing

Arbus’s subjects are almost always centered and photographed head-on, often staring directly into the camera. This compositional choice removes the illusion of spontaneity and invites psychological confrontation. There is no escape for the viewer—just as the subject is fixed, so too are we.

This frontal gaze also disrupts the “invisible photographer” ideal. Arbus doesn’t pretend to disappear. Her presence is felt in every image, as if her subjects are not just being observed but are acknowledging and reacting to the camera itself.

Flat Lighting and Minimal Contrast

While many photographers use shadow and directional light to sculpt or dramatize the subject, Arbus frequently employed even, flat lighting, often with the aid of a flash. This created a heightened sense of plainness, which paradoxically emphasized the emotional drama within the image.

Flat lighting removed illusion, glamor, and depth—there was no cinematic flair, only a direct encounter. This technique underscored her interest in truth without decoration.

Hyperreal Detail

The clarity afforded by her medium-format Rolleiflex, paired with her restrained post-processing, resulted in prints that were hyperreal in their detail. Facial pores, makeup smudges, chipped nail polish, and creased clothing all came through with unflinching clarity.

This level of detail denied romanticism and presented subjects as intimately real, reinforcing the viewer’s awareness of both their physical presence and psychological complexity.

Emotionally Ambiguous Mood

Arbus’s images carry an aura of emotional ambiguity. They rarely smile. They do not offer comfort. Instead, they evoke a mood of quiet discomfort, vulnerability, or tension. Even her child portraits seem tinged with unease or premature self-awareness.

This emotional ambiguity became a defining element of her style. It challenged viewers to go beyond surface interpretations and confront the inner turmoil or complexity behind the eyes of her subjects.

Minimalist Backgrounds

Though many of her images are set in bedrooms, parks, or public spaces, Arbus often worked with neutral or uncluttered backgrounds, allowing the subject to dominate the frame. The space was not the story—the person was.

This minimalist environment, combined with her direct composition, created a gallery-like effect: each individual framed as a subject of cultural, philosophical, and emotional inquiry.

9. BREAKING INTO THE ART MARKET

Diane Arbus’s rise within the art market was slow, then meteoric. Initially seen as controversial—even disturbing—her work defied the conventions of portraiture and the expectations of mid-20th-century American photography. But with her inclusion in major exhibitions and the support of influential curators, she became one of the first American photographers to be embraced by the fine art market in a serious and sustained way.

Early Institutional Support

Though she had published editorially in magazines like Esquire and Harper’s Bazaar, Arbus’s first major institutional breakthrough came with the 1967 MoMA exhibition New Documents, curated by John Szarkowski. Alongside Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, Arbus’s inclusion marked a turning point in how photography was framed—as personal, expressive, and art-worthy rather than merely journalistic.

Her portraits stood out for their rawness, psychological impact, and their intense—sometimes controversial—human engagement.

Posthumous Explosion

While Arbus had begun to gain recognition during her lifetime, it was only after her tragic death by suicide in 1971 that the art world began to truly reckon with the depth and originality of her work. The 1972 MoMA retrospective, held just one year after her death, attracted more than 250,000 visitors—a record for any photographic exhibition at the time.

This retrospective was accompanied by the publication of Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, which became one of the most influential photography books ever published. It introduced her vision to a global audience and became a staple in art schools, galleries, and collector libraries.

Gallery Representation and Auction Market

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Arbus’s work became a regular feature in major photography auctions. She has been represented by top-tier galleries such as Pace/MacGill, Fraenkel Gallery, and more recently by the David Zwirner Gallery, which assumed representation in 2022.

Her vintage prints—especially those printed and signed during her lifetime—are considered extremely rare and highly collectible. Modern estate-authorized prints, produced by her daughter Doon Arbus and the Diane Arbus Estate, also command significant prices, though usually less than lifetime prints.

Market Milestones

In 2005, Arbus’s print of Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey sold for $478,000 USD at Sotheby’s, breaking records for a female photographer at the time. In the years since, that image and others have continued to fetch prices in the $300,000–$600,000 USD range for early prints.

The most recent major auction sales have exceeded $800,000 USD for rare vintage prints of her most iconic works. Demand continues to grow, particularly among collectors focused on postwar American photography, feminist art, and socially engaged documentary work.

Foundation and Legacy Support

The Diane Arbus Estate, managed by her daughter and collaborators, plays an active role in controlling reproduction, authorizing exhibitions, and releasing limited edition prints. This level of control helps maintain market confidence and ensures that Arbus’s legacy remains coherent and protected.

Her enduring relevance in contemporary photography, combined with the scarcity of authentic vintage prints, has positioned her as one of the most valuable and widely collected photographers of the 20th century.

Discover the Spirit of COUNTRY AND RURAL LIFE

“Rustic simplicity captured in light, colour, and heartfelt emotion.”

Black & White Rural Scenes ➤ | Colour Countryside ➤ | Infrared Rural Landscapes ➤ | Minimalist Rural Life ➤

10. WHY PHOTOGRAPHY WORKS ARE SO VALUABLE

Diane Arbus’s photographs are some of the most emotionally powerful and financially significant works in the realm of fine art photography. Their high value is attributed not only to her iconic status but also to a convergence of artistic, historical, psychological, and cultural factors. Collectors and institutions alike view her work as a pillar in the evolution of modern photography.

1. Bold Subject Matter and Cultural Significance

Arbus photographed people who were traditionally unseen—or deliberately ignored—by mainstream culture. Her portraits of marginalized individuals introduced a new dimension of inclusivity and psychological realism into the photographic canon. These were not images designed to soothe or flatter, but to provoke and deepen understanding.

The cultural relevance of her subjects—from drag queens to circus performers, from twins to people with disabilities—makes her work both a historical document and a timeless commentary on identity, perception, and societal norms.

2. Psychological Depth and Viewer Engagement

Unlike traditional portraitists who focus on physical likeness or social status, Arbus portrayed emotional and psychological truth. Her portraits invite not only observation but deep introspection, often leaving viewers unsettled, curious, or transformed.

This capacity to stimulate emotional and intellectual dialogue elevates her photographs beyond mere images into experiences. That transformation of the viewer into a participant in the photograph is part of what gives her work enduring value.

3. Rarity of Vintage Prints

Vintage prints of Arbus’s work—those created and signed during her lifetime—are extraordinarily rare, especially considering her relatively short career. These prints are museum-grade collectibles, and their scarcity drives prices into the high six-figure range.

Her estate-managed posthumous prints, though more abundant, are produced in limited, meticulously controlled editions and continue to appreciate in value, particularly those issued in conjunction with major exhibitions or museum retrospectives.

4. Institutional Endorsement and Academic Canonization

Arbus’s work has been featured in retrospectives at major institutions including MoMA, the Met, Tate Modern, and Jeu de Paume. Her inclusion in global university curricula further strengthens her cultural and academic credibility, which significantly contributes to long-term investment appeal.

Collectors are more likely to invest in artists with established critical frameworks and institutional support, and Arbus ranks among the most rigorously analyzed figures in photographic history.

5. Auction Performance and Consistency

Over the last two decades, Arbus’s works have consistently sold in the $50,000–$600,000+ USD range depending on edition, condition, provenance, and subject matter. Her top images remain highly liquid and are frequently sold at blue-chip auctions, giving collectors reassurance of market stability.

This predictability in performance, combined with the upward trajectory of prices, classifies her work as a prime asset in the collectible photography market.

6. Emotional Branding and Cultural Icon Status

Arbus’s name carries immense emotional and symbolic capital. Her work is known even among people with limited knowledge of photography. Her images evoke strong reactions and have become part of the broader cultural lexicon. This type of brand recognition, paired with ethical depth and emotional weight, ensures that her work resonates across generations.

11. ART AND PHOTOGRAPHY COLLECTOR AND INSTITUTIONAL APPEAL

Diane Arbus’s photographs enjoy immense collector and institutional appeal. Few photographers have achieved such enduring cross-market recognition, attracting both traditional fine art investors and progressive collectors interested in psychological, sociological, or identity-based narratives.

1. Institutional Acquisition and Global Exhibition

Arbus’s works are held in the permanent collections of the world’s most important museums, including:

-

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

-

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

-

The Art Institute of Chicago

-

The Getty Museum, Los Angeles

-

Tate Modern, London

-

Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris

This level of institutional validation places her among the most respected photographers globally, elevating her market credibility and appeal to museum-level collectors.

2. Ideal for High-Concept Collectors

Collectors interested in identity politics, feminist art, LGBTQ+ history, or outsider narratives find Arbus’s work especially compelling. She is often described as the “photographer of the other,” and her body of work serves as a crucial record of cultural shifts and taboos in mid-20th century America.

This has made her a staple among collectors who focus on intersectionality, gender theory, psychology, and marginalized voices in art.

3. Broad Market Reach

Arbus’s work appeals to both high-end fine art buyers and socially conscious collectors. Her images are emotionally intense, aesthetically minimal, and universally compelling—qualities that allow them to function equally well in private homes, galleries, museums, and academic settings.

The emotional honesty in her work also makes it suitable for hospitality and healthcare spaces, where profound storytelling is valued as part of the environment.

4. Estate-Managed Print Consistency

The Diane Arbus Estate, administered by her daughter Doon Arbus and collaborators such as Neil Selkirk, maintains a strict policy for posthumous prints. These prints are released in limited editions with tight curatorial control, helping preserve the integrity, scarcity, and authenticity of her oeuvre.

This structured release program has made Arbus prints safe and reliable acquisitions for private collectors and institutions alike.

5. Emotional and Intellectual Legacy

Collectors often describe owning an Arbus print as owning a piece of human inquiry—not just an image, but a window into the fundamental questions of identity, gaze, and perception. This dual engagement with intellect and emotion gives her work unique gravitas in the market.

Many collectors view Arbus’s photographs as conversation pieces—works that spark debate, introspection, and social critique. In this sense, owning an Arbus is not merely an investment in art but an investment in cultural dialogue.

12. TOP-SELLING WORKS, MAJOR EXHIBITIONS AND BUYERS (WITH CURRENT RESALE VALUES)

Diane Arbus’s top-selling works are now legendary—each an emotionally intense and historically significant image that reflects her revolutionary approach to portraiture. Below are her most famous images, recent market performances, and updated resale estimates:

1. Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey (1967)

Description: Perhaps Arbus’s most iconic image, this portrait features two twin girls dressed identically, standing side by side. Their near-identical features and haunting expressions evoke both unity and tension.

-

Current Resale Value: $300,000–$650,000 USD (vintage); $80,000–$150,000 (estate print)

-

Exhibited At: MoMA, Tate Modern, The Met

-

Notable Buyer: A vintage print was acquired by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

2. Child with a Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, NYC (1962)

Description: A young boy glares wildly at the camera while gripping a toy grenade, his body twisted in agitation. The image captures psychological tension and societal unease during the Cold War era.

-

Current Resale Value: $250,000–$500,000 USD (vintage); $75,000–$125,000 (estate print)

-

Exhibited At: Jeu de Paume (Paris), Art Institute of Chicago

-

Auction Highlight: Sotheby’s New York (2022) – vintage print sold for $398,000

3. A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, NYC (1966)

Description: A portrait of a transgender individual preparing for transformation, seated in a cluttered room. The image challenges notions of gender, identity, and performance.

-

Current Resale Value: $180,000–$350,000 USD (vintage); $55,000–$100,000 (estate print)

-

Exhibited At: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Barbican Centre

-

Notable Buyer: Private New York-based gender studies collector

4. Mexican Dwarf in His Hotel Room, NYC (1970)

Description: A dwarf man lounges on his bed, wearing nothing but underwear and boots, surrounded by mundane hotel furniture. It is one of Arbus’s most intimate and controversial works.

-

Current Resale Value: $200,000–$400,000 USD

-

Exhibited At: Venice Biennale (1972), MoMA retrospective

-

Auction Highlight: Christie’s New York (2019) – sold for $310,000

5. A Jewish Giant at Home with His Parents in The Bronx (1970)

Description: A towering man, standing under a low ceiling, looms over his seated, elderly parents. The portrait plays with visual scale and emotional power, exploring love, alienation, and identity.

-

Current Resale Value: $180,000–$320,000 USD

-

Exhibited At: MoMA, The Met, Brooklyn Museum

-

Notable Buyer: Acquired by The Jewish Museum, New York

Major Exhibitions

-

Diane Arbus: Revelations – SFMoMA, MoMA, The Met

-

In the Beginning – The Met Breuer (2016–2017)

-

New Documents – MoMA (1967, with Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander)

-

Diane Arbus: A Box of Ten Photographs – Smithsonian American Art Museum

-

Untitled (Late Works) – David Zwirner Gallery, 2022

Immerse in the MYSTICAL WORLD of Trees and Woodlands

“Whispering forests and sacred groves: timeless nature’s embrace.”

Colour Woodland ➤ | Black & White Woodland ➤ | Infrared Woodland ➤ | Minimalist Woodland ➤

13. LESSONS FOR ASPIRING, EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Diane Arbus was not merely a photographer—she was a truth-seeker, a fearless observer, and a visual philosopher. Through her lens, she explored the fringes of society and illuminated the beauty, complexity, and vulnerability often overlooked in everyday life. Her work disrupted conventional aesthetics, giving voice to those on the margins and redefining what it meant to be seen.

For aspiring and emerging photographers, Arbus’s journey offers more than visual inspiration—it offers wisdom earned through emotional honesty, ethical depth, and creative risk. The following fifteen lessons drawn from her life and legacy are designed not only to refine your craft but to reshape how you see the world and your place in it as a visual storyteller.

Each lesson is grounded in Arbus’s own practice and philosophy, infused with quotes that echo her profound commitment to authenticity, curiosity, and connection. These are not just techniques—they are meditations on what it means to create with purpose, to see with empathy, and to engage with photography as both art and human encounter.

1. EMBRACE THE UNCOMFORTABLE AND UNKNOWN

Diane Arbus was renowned for her fearless exploration into realms that many found unsettling or even disturbing. Her willingness to delve into uncomfortable and unfamiliar situations was central to her distinctive photographic style. Arbus believed that true creativity required stepping into the unknown, confronting societal taboos, and engaging with marginalized communities. Her approach involved a profound level of personal vulnerability, openness, and curiosity, making her work resonate deeply with viewers and critics alike.

Arbus’s photographic philosophy was grounded in the idea that comfort and familiarity limit creative potential. She often remarked that her favorite experiences involved entering places she had never been before, emphasizing that genuine artistry emerges from such journeys into the unknown. Her photographs, characterized by stark realism and poignant humanity, offered viewers an intimate glimpse into lives and situations rarely represented in mainstream media or art.

This commitment to exploring uncomfortable subjects was not merely a professional choice but a deeply personal conviction. Arbus struggled with her own emotional complexities and mental health issues, experiences that perhaps deepened her sensitivity and empathy towards others who existed on society’s fringes. She approached these subjects not as outsiders or oddities but as fellow humans with stories worth telling, creating works imbued with dignity and respect.

For emerging photographers, this lesson from Arbus underscores the importance of pushing personal boundaries and confronting internal fears. Great photography often comes from challenging oneself to face unfamiliar environments, unusual subjects, or difficult emotions. By engaging directly with discomfort, photographers can access deeper levels of emotional authenticity and artistic originality.

Moreover, Arbus’s experiences highlight how embracing discomfort can lead to significant personal and creative growth. The act of stepping outside one’s comfort zone is not merely about capturing novel images but about fostering internal transformation. The willingness to confront what makes one uneasy or fearful often results in greater self-awareness, resilience, and compassion.

Philosophically, Arbus’s practice aligns closely with existentialist thought, which emphasizes the individual’s responsibility to engage authentically with life’s uncertainties and challenges. Existentialist thinkers argue that confronting discomfort and ambiguity is fundamental to developing a true sense of self. Arbus’s photography embodies this existentialist ideal, reflecting a courageous willingness to accept life’s inherent difficulties and complexities.

Life itself is inherently uncomfortable, filled with unpredictable challenges, conflicts, and moments of emotional vulnerability. Arbus’s work serves as a powerful reminder of this truth, encouraging photographers and viewers alike to embrace life’s difficulties as essential elements of human experience. Through her photographs, she demonstrated that discomfort is not something to avoid but rather something to explore and understand.

By embracing the unknown, photographers cultivate a spirit of adventure and discovery, essential traits for sustained artistic creativity. Photography, at its core, is an exploration of the human condition, and Arbus’s approach exemplifies how engaging with discomfort enriches one’s understanding of humanity. This perspective encourages photographers to view each uncomfortable experience as an opportunity to deepen their connection to their subjects and their own emotional landscape.

Additionally, Arbus’s philosophy resonates with contemporary ideas about vulnerability and authenticity, popularized by authors such as Brené Brown. Brown argues that true courage involves embracing vulnerability and uncertainty. Arbus’s life and work embody these principles, illustrating how vulnerability can become a powerful artistic tool. By allowing herself to be emotionally exposed and genuinely curious about her subjects, Arbus created deeply affecting works that continue to inspire photographers today.

This approach also invites photographers to re-evaluate their perspectives on failure and fear. Instead of viewing discomfort and uncertainty as barriers, they become essential components of artistic growth and creativity. Arbus’s legacy teaches that meaningful art often arises from the willingness to risk emotional exposure and confront societal taboos.

Emerging photographers are thus encouraged to adopt Arbus’s courageous mindset. Whether capturing marginalized communities, confronting societal issues, or simply challenging personal fears, embracing discomfort can lead to photographs that are profoundly impactful and emotionally resonant. The path to meaningful artistry is not found in avoiding discomfort but in confronting and exploring it deeply.

In summary, embracing discomfort and the unknown is central to creative and personal growth in photography. Diane Arbus’s fearless exploration of uncomfortable subjects exemplifies how facing fears and uncertainties enriches artistic practice. Her legacy serves as a powerful reminder to photographers of the value of vulnerability, authenticity, and courage. Aspiring photographers who follow this principle not only enhance their creative vision but also deepen their understanding of themselves and the complex world around them.

Quote: “My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been.”

2. SEE THE EXTRAORDINARY IN THE ORDINARY

Diane Arbus possessed an extraordinary ability to see beyond the surface of everyday life, finding profound beauty and meaning in ordinary people, places, and moments. Her photographic vision challenged the common perception that only dramatic or exceptional subjects could be worthy of artistic attention. Arbus demonstrated consistently through her images that even the most mundane or overlooked scenes could be deeply evocative and revealing.

Aspiring photographers can learn significantly from Arbus’s approach, understanding that creativity often lies in noticing and capturing the subtle and seemingly insignificant details of life. Her philosophy was grounded in the belief that everything—and everyone—has inherent value and a story worth telling. She approached each subject, no matter how commonplace, with intense curiosity and genuine empathy, uncovering layers of emotional complexity and humanity.

Arbus’s photographic style exemplified a mindful presence, encouraging photographers to slow down and truly observe their surroundings. Rather than rushing to photograph overtly impressive subjects, Arbus teaches that extraordinary imagery arises from attentiveness to life’s quiet moments. Her careful, contemplative method allowed her to discover nuances often missed by others.

Philosophically, Arbus’s work aligns with the Zen concept of mindfulness, emphasizing the importance of being fully engaged with the present moment. This practice of deep observation enables photographers to perceive ordinary scenes with fresh eyes, recognizing hidden significance and capturing compelling narratives that resonate deeply with viewers.

Seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary also calls for the suspension of judgment. Arbus’s subjects were often people who did not conform to societal expectations—dwarfs, giants, transgender individuals, circus performers, and people with disabilities. Yet she photographed them without sensationalism. Instead, she captured them with a sincere eye, seeking to understand and reveal their truth rather than project her own narrative.

For Arbus, the lens was not a barrier but a bridge. It allowed her to connect with her subjects and discover what made them beautifully human. In doing so, she helped redefine what was seen as valuable, remarkable, or beautiful in a photograph. This is a crucial lesson for photographers learning to navigate a world increasingly obsessed with perfection, filters, and surface-level aesthetics.

Her ability to portray the poignancy and dignity of those she photographed inspired a new visual language in photography—one that values honesty over glamour and depth over superficial charm. She taught that storytelling is not about embellishing or dramatizing but about recognizing what is already there, just beneath the surface, waiting to be seen.

For emerging photographers, this lesson is transformative. It encourages them to shift their perspective: to slow down, observe, and truly see. Often, the most emotionally resonant and philosophically rich images are those that portray life as it is, not as it should be. By embracing this principle, photographers learn to tell stories that are authentic, vulnerable, and relatable.

This perspective also cultivates a sense of empathy, one of the most important qualities a photographer can possess. Arbus’s portraits invite the viewer to feel with the subject, not just look at them. They challenge the observer to question what they see and confront their assumptions about normalcy, beauty, and difference.

In an age saturated with polished imagery and curated realities, Arbus’s commitment to capturing the raw and unembellished has become even more relevant. Emerging photographers can take inspiration from her fearlessness in pursuing subjects that others ignored, and in doing so, they can help expand the scope of visual storytelling in today’s world.

Arbus once said, “The world can only be grasped by action, not by contemplation… The most decisive essential act of our tiny lives is to create.” This act of creation is grounded in perceiving and honoring the extraordinary within the ordinary. It’s an invitation to all artists to engage with the world not just through their cameras, but through their hearts and intuition.

Arbus’s legacy teaches that great photography is not about sensationalism but about presence. It’s not about capturing what everyone sees, but about revealing what others miss. When photographers begin to recognize the emotional resonance in the overlooked details of daily life, they develop a voice that is quiet yet powerful, humble yet evocative.

Philosophical Reflection: Arbus’s work evokes questions about perception, reality, and the value society places on appearances. It urges us to interrogate our own biases and ask why we overlook certain people or moments. Her commitment to seeing deeply reveals photography’s potential not just as an art form, but as a tool for expanding empathy and awareness.

Life Reflection: Seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary is a life practice as much as it is an artistic one. It teaches mindfulness, gratitude, and the ability to find meaning in the everyday. For photographers and non-photographers alike, this lesson encourages a more engaged and compassionate way of living.

Quote: “The more specific you are, the more general it’ll be.”

3. AUTHENTICITY IS YOUR GREATEST ASSET

In an era increasingly influenced by image manipulation, social media curation, and staged aesthetics, Diane Arbus’s work stands as a powerful reminder of the raw value of authenticity. Her photography was deeply personal and unfiltered, portraying her subjects with uncompromising honesty. Arbus once said, “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know,” a statement that encapsulates her philosophy about the elusive nature of truth and the role of the photographer in chasing it.

For aspiring photographers, authenticity is not just a stylistic choice—it is the cornerstone of a meaningful and enduring photographic practice. Authenticity requires vulnerability. It demands that the photographer show up as their truest self and that they extend the same grace to their subjects. In Arbus’s case, this meant working with individuals who defied conventional ideals of beauty, normality, or acceptability. Her portraits of people living on the margins of society—whether physically, psychologically, or culturally—offered a glimpse into the extraordinary diversity of human experience.

What made Arbus’s work so profound was not merely her choice of subject but her refusal to alter, dramatize, or beautify the reality she encountered. She photographed people in their own environments, on their terms, and in their own time. She didn’t attempt to erase flaws or construct fictional narratives. Instead, she documented truth—sometimes uncomfortable, sometimes surreal, but always real.

This honesty transformed her camera into a mirror not only for the subject but also for the viewer. Her images provoke questions, stir empathy, and invite contemplation. They force us to confront our biases and broaden our understanding of what it means to be human. Arbus’s dedication to authenticity illustrates that real connection begins when pretense ends.

For photographers just beginning their journey, there may be temptation to mimic popular styles or trends in search of validation. But Arbus teaches that the path to lasting impact lies in resisting conformity and listening to one’s inner vision. Authenticity is not about being different for the sake of it—it is about being deeply aligned with one’s creative instincts and values.

Philosophically, Arbus’s commitment to authenticity intersects with existentialist ideas that champion self-definition and personal responsibility. In the words of Jean-Paul Sartre, “Existence precedes essence.” Arbus embraced existence in all its chaotic, messy, imperfect glory and made it the essence of her work. She reminds us that the truth of a moment or a person is far more compelling than any constructed illusion.

Arbus’s life was also marked by emotional struggles, including depression, alienation, and a lifelong sense of otherness. Yet rather than concealing this pain, she seemed to channel it into her art. The authenticity in her work was mirrored in her personal openness to emotion—both her own and others’. This symbiotic relationship between life and art reveals how embracing one’s full emotional spectrum enriches artistic depth.

Technically, authenticity can also be seen in Arbus’s use of medium-format cameras and natural lighting. These tools allowed her to be present in the moment, to engage more deeply with her subjects, and to avoid distractions. The deliberate nature of her process underscored her intent to honor what was real, rather than chase what was popular.

In practical terms, authenticity might look like photographing one’s community, documenting personal experiences, or capturing the lives of people whose stories are often ignored. It’s about rejecting the myth that only “important” subjects deserve attention. Arbus proved that authenticity itself transforms any subject into something profound.

Moreover, authenticity creates trust—not only between the photographer and the subject but also between the photographer and the viewer. When a photographer is honest, the viewer senses it. There is a transparency, a soul, that cannot be faked or replicated. This trust, once established, allows the image to resonate across boundaries of time, culture, and context.

Arbus’s lesson for emerging photographers is to trust that their vision, no matter how unconventional, is enough. They don’t need permission to be themselves or to explore what genuinely moves them. They only need courage—the courage to be honest, even when it’s uncomfortable.

Her portraits are not just images; they are emotional testaments. They teach that authenticity isn’t about perfection. It’s about presence. It’s about being willing to see and be seen. It’s about recognizing the sacredness of truth in a world often preoccupied with illusion.

Philosophical Reflection: Arbus’s work reminds us that photography is a dialogue between truth and perception. Her commitment to honesty challenges photographers to explore their own motivations and to embrace the unpolished realities of life. In doing so, they don’t just take pictures—they bear witness.

Life Reflection: Living authentically, like photographing authentically, is not easy. It requires self-awareness, acceptance, and a willingness to be misunderstood. But it is also deeply rewarding, building a life—and a body of work—that is rich, resonant, and real.

Quote: “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.”

Journey into the ETHERAL BEAUTY of Mountains and Volcanoes

“Ancient forces shaped by time and elemental majesty.”

Black & White Mountains ➤ | Colour Mountain Scenes ➤

4. BUILD INTIMATE CONNECTIONS WITH YOUR SUBJECTS

Diane Arbus’s photographic success was deeply rooted in her ability to forge genuine, intimate relationships with her subjects. This connection went beyond technical composition or aesthetic choices—it touched on the emotional, spiritual, and psychological levels of engagement. Her camera became an extension of her ability to communicate, to empathize, and to honor the human experience. She once said, “For me, the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture.”

For aspiring photographers, this lesson is pivotal. Technical skill may draw the eye, but it is emotional authenticity that holds attention. Building intimacy with a subject means creating a safe space for vulnerability, not only for them but also for yourself. Arbus’s portraits resonate because they carry the energy of mutual trust, shared experience, and unspoken understanding. Her subjects weren’t merely documented; they were revealed, often in their rawest and most dignified forms.

Arbus was not a distant observer. She immersed herself in the lives of her subjects. Whether photographing people at nudist camps, drag performers backstage, or individuals with disabilities, she was fully present, attentive, and compassionate. Her presence allowed subjects to relax, to unfold, and to share aspects of themselves not typically visible to outsiders. This vulnerability, once captured, became the essence of her work’s power.

Intimacy in photography is not about proximity—it’s about connection. A photograph can be physically close but emotionally distant. Arbus teaches us to strive for emotional closeness, to see not only with our eyes but with our hearts. Emerging photographers must learn to be listeners, confidants, and observers in equal measure. Only then can the soul of the subject emerge.

Philosophically, this lesson intersects with the ethics of representation. When we photograph someone, we are engaging in a powerful act of interpretation. The responsibility lies in ensuring that the representation is respectful, honest, and compassionate. Arbus’s work demonstrates that intimacy leads to deeper truths—ones that statistics, headlines, or distance cannot capture.

Developing intimacy also requires time. Arbus often spent extended periods with her subjects before even lifting her camera. This patience allowed her to enter their world, to understand their rhythms, and to allow authenticity to surface naturally. For new photographers conditioned by instant gratification and quick content, Arbus’s method is a powerful reminder that profound images require presence, not haste.

Furthermore, building intimacy involves emotional risk. To connect with another person, especially someone whose life may be vastly different from your own, requires confronting your fears, biases, and assumptions. Arbus was not immune to this. She was drawn to people she found both fascinating and alien. But instead of maintaining distance, she leaned in. That courage to connect—to reach beyond oneself—is what transformed her work from documentary into art.

Intimacy also shapes the viewer’s experience. When a photographer has established a deep connection with their subject, it’s almost as if the viewer can feel it too. There’s a resonance in the gaze, the posture, the silence. Arbus’s images are not just viewed; they are felt. This emotional transference is what elevates a photograph from visual record to visual poetry.

Technically, Arbus often used a twin-lens reflex camera held at waist level, allowing her to maintain eye contact with her subjects. This seemingly simple choice made a profound difference. It eliminated the barrier of the viewfinder and facilitated more natural interaction. For aspiring photographers, such subtle shifts in technique can foster greater comfort and collaboration with subjects.

Her practice also included asking permission, spending time listening, and respecting her subjects’ autonomy. She saw her subjects not as curiosities but as collaborators in the creative process. This mutual respect, this shared authorship, is the foundation of all intimate photography.

Philosophical Reflection: Arbus’s method prompts reflection on the ethics of intimacy. How do we approach another person with honesty, without exploitation? How do we document without dominating? Her work invites us to be humble, to be present, and to be willing to meet others where they are.

Life Reflection: Building intimacy is not only a photographic skill but a life skill. It teaches empathy, patience, and emotional intelligence. Whether behind the lens or not, the ability to forge meaningful connections enriches every human interaction.

Quote: “For me, the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture.”

5. CHALLENGE SOCIAL NORMS THROUGH YOUR WORK

Diane Arbus was a pioneer in challenging societal conventions and expanding the boundaries of what photography could express. Her images were unapologetically direct, often confronting viewers with subjects they were not accustomed to seeing in art galleries or magazines. She gravitated toward individuals marginalized by society—people whose appearances, lifestyles, or identities defied mainstream standards of beauty, gender, or behavior. Through her lens, Arbus didn’t simply document these individuals; she presented them with dignity, complexity, and nuance.

Her subjects included drag queens, people with dwarfism or gigantism, transgender individuals, circus performers, and individuals with intellectual disabilities. Rather than exoticizing or sensationalizing them, Arbus photographed them as equals, stripping away the viewer’s preconceptions and challenging societal taboos. Her work was sometimes described as controversial, but it was never exploitative—it was humanizing.

For aspiring photographers, this lesson is profound: photography is not just a craft—it is a form of social commentary. Photographers have the ability, and arguably the responsibility, to question what is accepted, to reveal what is hidden, and to give a voice to those who have been silenced. Challenging social norms doesn’t necessarily mean provoking outrage—it means prompting reflection, inviting dialogue, and encouraging empathy.

Arbus’s own life was emblematic of the tension between conformity and rebellion. Born into a wealthy Jewish family, she abandoned a comfortable life to pursue art that many in her social class found disturbing. This act of personal rebellion fed into her artistic philosophy. She believed that photography could and should reveal the parts of life that people often deny or ignore. She once said, “I want to photograph the considerable ceremonies of our present.”

Philosophically, her work aligns with the theories of cultural criticism and postmodernism, which seek to dismantle dominant narratives and elevate marginalized voices. Arbus understood that norms are not fixed truths but social constructs. By questioning these constructs, photographers can create more inclusive, authentic, and revolutionary art.

Technically, Arbus used direct, frontal compositions, minimal staging, and stark lighting to remove distractions and allow the viewer to confront the subject head-on. This confrontational style forced audiences to engage with the subjects as individuals rather than stereotypes. Her square-format photographs contributed to this sense of equilibrium and equality between viewer and subject.

Emerging photographers can learn from this by embracing the courage to explore controversial themes or to work with communities that are misrepresented in visual culture. It requires humility, ethical awareness, and a willingness to listen. But the rewards are immense—not only in terms of artistic growth but in contributing to a more compassionate and inclusive visual landscape.

Challenging norms through photography also means challenging oneself. Arbus did not stay within her comfort zone; she actively sought out subjects that made her feel something—whether awe, discomfort, admiration, or curiosity. This emotional engagement is what made her work resonate. She was not merely pointing a camera at the world; she was interrogating it.

Philosophical Reflection: Arbus’s work compels us to ask: What do we consider normal, and why? Who benefits from these definitions, and who is excluded? Her images encourage a more nuanced understanding of identity, pushing us toward greater openness and acceptance.

Life Reflection: To challenge norms in art is to challenge them in life. It involves confronting our own biases, stepping into unfamiliar spaces, and embracing the richness of human diversity. This process not only broadens our creative horizons but deepens our humanity.

Quote: “I want to photograph the considerable ceremonies of our present.”

6. CULTIVATE PATIENCE AND OBSERVATION

Diane Arbus’s artistry did not stem from hastiness or impulsiveness; rather, it was rooted in a deep commitment to patience and deliberate observation. Her images reveal not just the surface of her subjects, but layers of identity, emotion, and complexity that could only emerge through time, trust, and silent attentiveness. Patience allowed Arbus to wait for those moments of revealing—when the mask slipped, when the essence of her subject quietly emerged.

For aspiring photographers, patience is one of the most underestimated yet powerful tools. The rush to create, publish, or be noticed often leads many to overlook what lies just beneath the surface. But Arbus understood that the soul of a subject doesn’t reveal itself immediately—it unfolds slowly, sometimes hesitantly, like a flower reaching for light. This slow revelation requires the photographer to be still, to be present, and to wait without pressure.

Arbus’s patience extended to her process. She spent long hours with her subjects, often returning multiple times to photograph them, allowing a relationship to develop organically. This temporal investment built rapport and trust, crucial elements that helped dissolve the psychological distance between the camera and the subject. In doing so, Arbus was able to capture portraits that resonate with extraordinary authenticity and intimacy.

Observation, too, was integral to Arbus’s practice. But it was not passive observation. It was a kind of heightened awareness—a listening with the eyes. She noticed gestures, micro-expressions, the texture of skin, the posture of a body, the small tells that hinted at deeper emotional truths. In this way, Arbus’s photography became a study in human psychology, revealing not only who her subjects were but how they wished to be seen—and how they hoped not to be misunderstood.

This level of observation necessitates a slowing down of the photographic process. In a world that prioritizes speed, Arbus’s approach serves as a radical act of resistance. It tells young photographers that great images are not always made in bursts of creativity but in long stretches of quiet contemplation.

Philosophically, patience and observation tie into the broader existential and phenomenological frameworks that value presence, experience, and perception. The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty argued that true perception arises from embodied experience—that we come to know things by dwelling with them. Arbus’s photographs illustrate this principle: she dwelled with her subjects, physically and emotionally, until the truth of their being began to speak.

Her choice of equipment also facilitated this practice. Arbus used a medium-format Rolleiflex camera, which required a slower, more methodical approach to composition and focus. Unlike modern point-and-shoot or digital setups, this process demanded full attention, intentional framing, and careful exposure settings. Each shot was precious, each frame considered.

Emerging photographers who embrace patience and observation will find that their work matures with time. By allowing themselves to be still and attentive, they open the door to deeper emotional engagement and stronger narrative presence. This doesn’t mean they will always produce more images—it means they will produce better ones.

Arbus’s legacy in this regard reminds photographers that observation is not only about seeing—it’s about understanding. It’s about being curious without being intrusive, watchful without being controlling. When photographers observe with empathy and patience, they begin to see things others miss: the flicker of uncertainty in a subject’s eyes, the subtle pride in a gesture, the delicate tension between vulnerability and strength.

In a broader sense, this lesson also teaches that patience and observation are not limited to photography—they are life skills. They help us build better relationships, make wiser decisions, and find beauty in the slow, unfolding rhythm of the everyday. In learning to observe others, we also learn to observe ourselves.

Philosophical Reflection: Arbus’s quiet attentiveness aligns with meditative traditions and phenomenological thought, suggesting that art is not created in haste but in presence. By slowing down, we become more aware, more ethical, and more human.

Life Reflection: Cultivating patience enriches not only your craft but your character. It teaches you to listen more than speak, to feel more than assume, and to witness life in all its intricate complexity.

Quote: “The thing that’s important to know is that you never know. You’re always sort of feeling your way.”

Wander Along the COASTLINE and SEASCAPES

“Eternal dialogues between land, water, and sky.”

Colour Coastal Scenes ➤ | Black & White Seascapes ➤ | Minimalist Seascapes ➤

7. VALUE YOUR UNIQUE PERSPECTIVE

One of the most enduring legacies of Diane Arbus is her unwavering belief in the importance of personal vision. At a time when traditional beauty and conformity were the norms in visual media, Arbus stood apart by embracing what others ignored, rejected, or feared. Her photographs—deeply intimate, strange, and unapologetically honest—reminded the world that uniqueness is not only valid but also vital. For emerging photographers, this principle serves as a profound and empowering lesson: your point of view is your greatest creative asset.

Arbus once said, “I really believe there are things nobody would see if I didn’t photograph them.” In this one statement lies a philosophy of radical artistic individuality. She understood that the way she saw the world—her curiosities, her discomforts, her questions—mattered. She believed that every artist has a unique window through which they interpret life, and that window deserves to be honored and developed, not blurred through imitation or conformity.

For young photographers starting out, the pressure to mimic popular trends or acclaimed artists can be immense. Social media algorithms, gallery expectations, and peer validation can inadvertently steer artists away from their own vision. Arbus’s work insists on the opposite: dig deeper into what makes you different, not what makes you similar.

Cultivating your unique perspective means tuning into your instincts, your values, and your curiosities. It may involve exploring your own identity, delving into personal history, or engaging with subjects that resonate emotionally or philosophically. For Arbus, it meant engaging with people and scenes that reflected her own sense of alienation, fascination, and empathy.

This pursuit requires courage. Standing by your unique perspective means accepting that not everyone will understand your work. Some might find it unsettling. Others might challenge your intentions. Arbus faced this often, but she never veered away from her truth. Her images spoke volumes precisely because they were so intimately hers—no filter, no compromise.

Philosophically, this lesson aligns with existentialist and postmodern theories that question the existence of universal truths and instead emphasize individual experience and perspective. In a postmodern lens, truth becomes plural, subjective, and fragmented—much like the world Arbus captured. Her photography reflected this multiplicity and made space for alternative narratives.

Technically, Arbus’s approach also reflected her singular perspective. She would often use a square-format Rolleiflex camera, which forced a more symmetrical and centered composition, subtly reinforcing her subjects’ presence and equality within the frame. Her lighting, choice of subject, and direct framing techniques weren’t just stylistic—they were deeply intentional reflections of how she saw the world.

Emerging photographers should take this to heart. The tools you choose, the subjects you engage with, the stories you tell—they should all flow from who you are and how you see. The moment you start chasing someone else’s idea of success or beauty, you begin to lose the most powerful thing you have: your voice.

To value your unique perspective is also to commit to constant self-inquiry. Ask yourself: What do I care about? What moves me? What scares me? What angers me? What stories do I wish someone would tell? Then go tell them. Use your photography not only to share what you see but to process what you feel and believe.

Arbus’s career illustrates that artists who embrace their individuality contribute something lasting and meaningful to the world. Her work continues to inspire generations not because she followed rules, but because she broke them—intelligently, purposefully, and with conviction.

Philosophical Reflection: This lesson speaks to the heart of artistic authenticity. By honoring your unique perception, you resist the homogenizing forces of mass culture and instead offer a vision that is original and irreplaceable. In doing so, you claim your space in the world and give others permission to do the same.

Life Reflection: Embracing your uniqueness extends far beyond photography. It is a life practice—a declaration that your perspective is not only sufficient but significant. This mindset fosters self-respect, resilience, and the courage to walk your own path.

Quote: “I really believe there are things nobody would see if I didn’t photograph them.”

8. DEVELOP YOUR CREATIVE CURIOSITY

Diane Arbus’s life and work were driven by an unrelenting curiosity—a desire to see, understand, and explore beyond the surface of ordinary life. She believed that creativity was not a gift bestowed upon the lucky few, but a skill honed by relentless questioning and a hunger for discovery. For Arbus, curiosity wasn’t passive; it was a mode of being. It pulled her toward people and places others might avoid, and it enabled her to create images that captured the essence of human strangeness and familiarity alike.

For emerging photographers, curiosity is both compass and fuel. It guides the lens, informs choices, and provides the energy necessary to venture beyond the safe and the known. Arbus reminds us that to remain creatively curious is to remain alive as an artist. Her choice of subjects—from sideshow performers to children in Central Park to everyday families—was never random. She followed questions rather than answers, intuition rather than expectation.

Arbus once said, “My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been.” That sentiment wasn’t just about physical travel—it was about psychological, emotional, and intellectual exploration. She sought out what was hidden, obscure, or misunderstood. And she did so not with judgment, but with a desire to connect, to see others fully, and perhaps even to better understand herself.

Creative curiosity involves risk. It asks photographers to confront what they do not know, and to acknowledge that their assumptions may be wrong. But this risk is also a tremendous gift. It opens the door to new visual languages, new relationships, and new modes of storytelling. It moves the photographer from documenting to discovering.